Tyrannosaurus rex: Fearsome Hunter, Scavenger, or Both?

Tyrannosaurus rex is one of the most famous dinosaurs, often depicted as the ultimate predator. But paleontologists have long debated whether T. rex was an active hunter, a scavenger, or a bit of both. In this article, we’ll explore the scientific evidence on both sides of the debate. We’ll see what T. rex’s bones, teeth, and even fossilized poop tell us about how this giant carnivore really lived. By the end, you’ll understand why most scientists today believe T. rex was neither strictly a hunter nor strictly a scavenger, but an opportunist that did whatever it needed to survive.

The question of T. rex’s feeding behavior has captured public imagination for decades. Was the “Tyrant Lizard King” a ferocious predator that hunted live prey, or a wimpy scavenger that only fed on animals already dead? In the 1990s, paleontologist Jack Horner famously argued that T. rex might have been primarily a scavenger, challenging the classic view of T. rex as a fearsome hunter. This sparked a lively debate in paleontology. Let’s look at the arguments on each side.

Horner’s Scavenger Hypothesis

Horner and a few others pointed to several features of T. rex’s anatomy and environment that, in their view, suggest it was better suited for scavenging than hunting. Some of the key arguments from the scavenger camp include:

Tiny Arms: T. rex’s arms were famously small relative to its body. Horner argued the arms were too small to grapple prey, so T. rex wouldn’t be effective in a fight. If the animal fell during a chase or struggle, its little arms couldn’t break the fall, risking serious injury This suggests T. rex might avoid combat and stick to scavenging.

Bone-Crushing Teeth: Unlike the blade-like teeth of other predators, T. rex had thick, robust teeth. Horner noted that such dental “tools” would be great for crunching through bones and tough carcass scraps left behind by other hunters. In his view, T. rex’s teeth were like the can-openers of the dinosaur world – perfect for getting at bone marrow and sinew in a dead carcass, rather than slicing fresh meat.

Built for Walking, Not Running: The leg bones of T. rex show that the thigh bone (femur) is longer than the shin bone (tibia). In fast-running animals, it’s often the opposite. Horner argued that this proportion indicates T. rex couldn’t run fast If it was too slow to catch agile prey, scavenging meals that couldn’t run away would make more sense.

Keen Nose, Poor Eyes? Endocasts (brain cavity casts) of T. rex’s skull show very large olfactory bulbs (brain areas for smell) and initially were thought to show a smaller optic lobe (vision center). Horner likened T. rex’s brain to that of a vulture – excellent at sniffing out carcasses from far away, but not built for keen eyesight . A strong sense of smell is extremely useful for a scavenger locating dead animals, while a predator would need sharp vision to hunt.

Lack of Healing Wounds: Perhaps the most dramatic claim: Horner noted that at the time, no fossils showed clear healed bite wounds from T. rex. If T. rex regularly attacked living animals, we would expect to find an occasional survivor with a healed T. rex bite mark. Instead, all known bite marks appeared to be on dead animals (with no healing). This was used to suggest T. rex was only feeding on carcasses after the prey was already dead.

Horner’s hypothesis was certainly provocative – after all, it turned the image of T. rex as a fearsome predator on its head. However, most paleontologists did not find these arguments convincing on their own Let’s examine the counter-evidence and the traits of T. rex that point to an active hunter.

The Case for T. rex the Hunter

Most scientists maintain that T. rex was an apex predator – the top hunter of its environment – that would also scavenge when it had the chance. They argue that many features of T. rex’s body and new fossil discoveries support its hunting abilities:

Eyesight Built for Hunting: Far from having poor vision, T. rex had forward-facing eyes that gave it depth perception (overlapping fields of view), much like modern hawks or lions. A study using facial reconstructions and perimetry found T. rex had a binocular vision range of about 55°, surpassing that of a hawk CT scans of its skull show a well-developed optic nerve, suggesting T. rex’s eyesight was as good as that of an eagle or other bird of prey Good eyesight and depth perception are traits found almost exclusively in predators, helping them judge distance when striking at prey. In short, T. rex likely had keen vision to track and attack living targets.

A Powerful Bite and Deadly Jaws: T. rex didn’t earn its reputation for nothing – its bite force was enormous. Researchers estimate T. rex had the most powerful bite of any land animal ever, capable of exerting tens of thousands of newtons of force. One simulation showed T. rex’s bite could be 114 times stronger than that of an average human. Its jaws were huge and muscular, anchored by massive attachment areas on the skull. The teeth, while thick, weren’t just blunt instruments – they had sharp serrated edges like steak knives, ideal for shearing flesh. This combination of thick, sturdy build and serrations meant the teeth could puncture deep and not snap, even when biting into bone In one estimate, a single chomp could rip away 500 pounds (~225 kg) of flesh in one go. Such a “perfect killing machine” head and bite make far more sense if T. rex was actively subduing prey, not just nibbling carrion.

Strong Legs (and Enough Speed): While T. rex might not have been a sprinter like a cheetah, it was no slouch. Its legs were long and built for locomotion, with evidence of large muscle attachments on the thigh bones Recent biomechanical studies estimate T. rex’s top speed around 20–25 mph (32–40 km/h)– about as fast as a charging rhinoceros. That’s easily quick enough to run down large herbivorous dinosaurs in its environment. Even if T. rex wasn’t the fastest dinosaur, it didn’t need cheetah-like speed. The Late Cretaceous landscape of North America had forests and obstacles where ambush tactics would be more useful than long chases T. rex could have been an ambush predator, capable of a quick burst to strike unwary prey. (And as one paleontologist quipped, according to muscle physics bumblebees shouldn’t be able to fly – yet they do.So we should be cautious in underestimating T. rex’s mobility.)

Not-So-Useless Arms: Those puny arms on T. rex might look comical, but they were extremely strong for their size. Each arm was about the length of a human arm but far more muscular, with studies suggesting each could lift over 180–200 kg (400+ lbs). The arms ended in two sharp claws. While they may not have been primary weapons, they could help hold prey close or aid the T. rex in standing up from a resting position. Importantly, T. rex was not alone in having small arms – many giant carnivorous dinosaurs evolved small forelimbs as their heads grew larger. In 2022, scientists described Meraxes, a distant cousin of Allosaurus, which independently evolved a large skull and stubby arms “to keep out of the way of struggling prey,” much like T. rex. This suggests short arms were an adaptation in big meat-eaters to prevent accidental injury during attacks, rather than evidence of a scavenging lifestyle. In other words, T. rex’s arms might be small, but that could be because it was such a lethal predator that mainly used its jaws to dispatch prey.

Brain and Senses: T. rex’s brain shows a complex mix of sensory strengths. We’ve noted its vision was likely very sharp, contrary to the notion of weak eyesight. And yes, its sense of smell was excellent – possibly the best of any dinosaur studied. But a great sense of smell doesn’t exclude active hunting; many predators (like wolves or sharks) rely on smell to track wounded prey or carcasses. T. rex’s big olfactory bulbs could have helped it sniff out live prey and dead bodies from miles away. In short, T. rex had a hunter’s toolkit: good eyes, a great nose, powerful jaws, and strong legs. Nothing in its biology outright prevents it from being a formidable predator.

Fossil Clues: Battle Scars and Bite Marks

While anatomy is informative, the smoking gun in the predator-or-scavenger question comes from the fossil record of behavior – bite marks, injuries, and other trace evidence left on bones. And this is where T. rex truly shows its hand as a hunter (while also taking advantage of carrion).

One of the most famous fossils related to this debate is a set of hadrosaur (duck-billed dinosaur) tail bones with a T. rex tooth stuck in them. In 2013, paleontologists reported a broken T. rex tooth crown embedded between two tail vertebrae of an herbivore (likely Edmontosaurus). Remarkably, the bone around the tooth had begun to heal, forming new growth. This means the hadrosaur was alive when T. rex bit it, got away, and lived long enough for the wound to start healing. In other words, it’s direct physical evidence of a T. rex attack on live prey. Paleontologist David Burnham called it the “holy grail” of T. rex behavior fossils – proof that “without a shadow of a doubt” T. rex engaged a living animal in combat. The discovery “essentially recrowned the king,” as one article put it, firmly re-establishing T. rex as an active predator.

This wasn’t an isolated case. Paleontologists have identified multiple examples of T. rex bite marks on other dinosaur bones, sometimes with healing. Several Triceratops (the three-horned dinosaur) skulls and frills have puncture wounds that match T. rex teeth. Some of these may show signs of healing, though once T. rex’s jaws clamped down, the victim likely didn’t survive long. One Triceratops pelvis was found with a large U-shaped chunk missing – something only a T. rex could have bitten out. It’s hard to imagine a “slow-moving scavenger” managing to take a bite out of a healthy, living Triceratops unless it was actively attacking it.

On the other side of the coin, there is evidence T. rex did scavenge when opportunity arose – including on its own kind. In a surprising 2010 study, researchers found unhealed T. rex bite marks on T. rex bones, indicating cannibalism. Apparently, T. rex wouldn’t hesitate to munch on a dead (or defeated) rival. This might sound gruesome, but it’s not unusual in nature – many top predators today, from lions to Komodo dragons, will scavenge or even eat members of their own species under desperate conditions. The fact that T. rex sometimes scavenged from carcasses (even of other T. rexes) fits the idea that it was an opportunistic feeder.

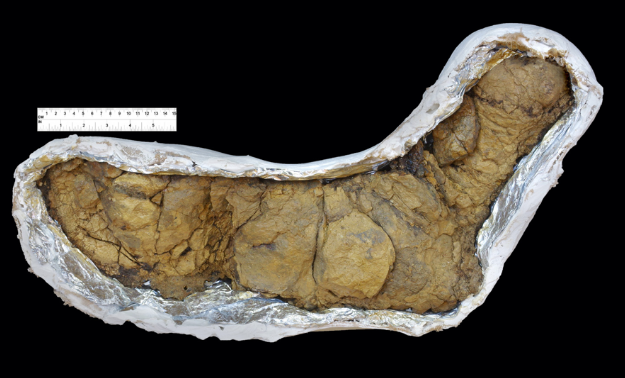

Another line of evidence comes from coprolites – fossilized dung. A famous T. rex coprolite (over two feet long!) was found packed with bone fragments from a juvenile duckbilled dinosaur. This tells us two things: T. rex was consuming bone along with flesh (something a predator that catches and devours prey might do, as would a scavenger finishing off a carcass), and it had a digestive system capable of handling crushed bone The ability to crunch and digest bone is rare but seen in some modern scavengers like hyenas. For T. rex, the presence of bone in its droppings suggests it didn’t pick or nibble daintily at prey – it went all-in, devouring even the less nutritious parts. Whether those bones came from an animal it killed or just found, we can’t say, but they underscore T. rex’s role as a bulk feeder of carcasses.

A large T. rex coprolite (fossil feces) from South Dakota, nicknamed “Barnum.” It measures 63.5 cm long. Chemical analysis showed high calcium and phosphorus, and it contains about 30–50% crushed bone pieces. This indicates T. rex could crunch through and ingest bones – a trait useful for extracting every bit of nutrition from prey or carrion.

An Opportunist Like No Other

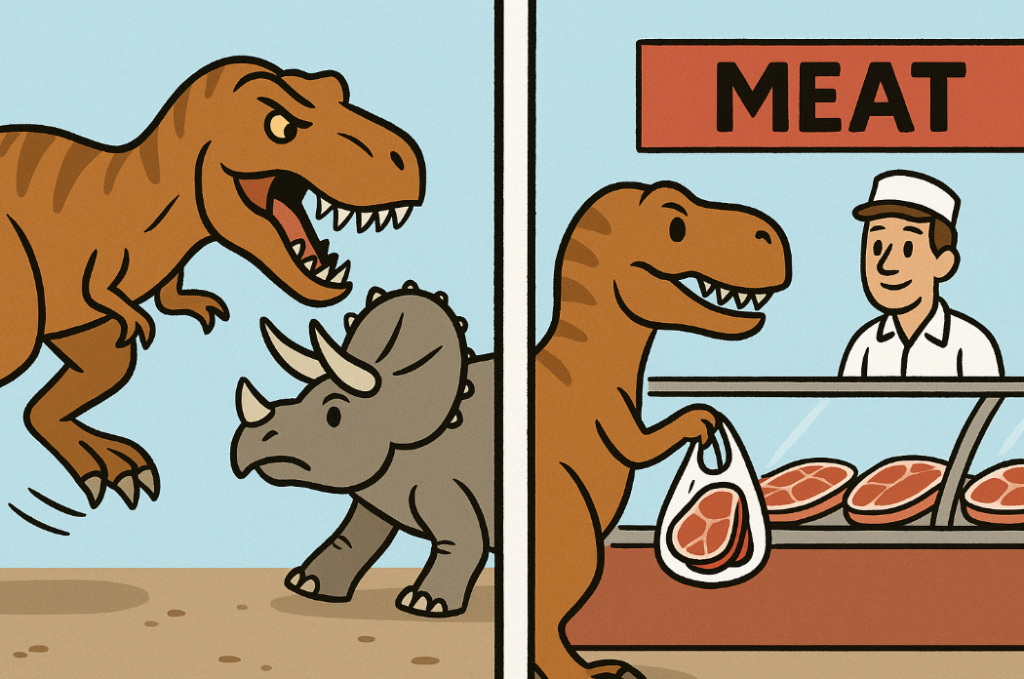

If all this evidence tells us anything, it’s that the predator-vs-scavenger dichotomy is too simple. T. rex was both a hunter and a scavenger, as most large carnivores are. Paleontologist Thomas Holtz summed it up by explaining that tyrannosaurs had adaptations for fast movement and active hunting, yet obviously would not pass up a free meal. In modern ecosystems, no top predator exclusively hunts or exclusively scavenges. Lions will scavenge kills from hyenas or wild dogs when they can. Hyenas, known scavengers, actually hunt a substantial portion of their food and will chase cheetahs off fresh kills. Bears, wolves, and big cats all happily eat carrion if they find it. As one writer quipped, “all top predators…will eat something that is already dead” if given the chance.

The T. rex likely exhibited similar behaviors. Due to its massive size—ranging from 7 to 9 tons—and remarkable strength, an adult T. rex could easily intimidate smaller predators, such as dromaeosaurs (raptor dinosaurs) or juvenile tyrannosaurs, allowing it to steal their kills. This strategy is known as kleptoparasitism. By employing this tactic, the T. rex could conserve energy, avoiding the risks associated with hunting when it could benefit from another’s efforts.

As T. rex matured from a slender, agile young dinosaur into a large adult, its feeding strategy may have evolved. Juvenile T. rexes were lighter and had longer legs relative to their bodies, which likely enabled them to chase down smaller prey. In contrast, as they grew bulkier, adult T. rexes might have ambushed larger prey or scavenged carcasses more frequently. This type of age-dependent diet is also observed in modern Komodo dragons: young Komodo dragons hunt insects and lizards, while adult dragons can take down larger animals, such as water buffalo, or scavenge from carcasses.

So, was T. rex a hunter or a scavenger? The best answer: it was both.. As one 2020 review for young readers put it, there are clear fossil examples of T. rex hunting and clear examples of scavenging, so it did whatever was necessary. T. rex was the apex carnivore of Late Cretaceous North America, and it didn’t attain that status by being picky. It had the tools to be a fearsome predator, and it used them – but if a juicy carcass was available, it would certainly not let it go to waste. In the end, scientists now generally agree that Tyrannosaurus rex was an active predator that also opportunistically scavengeden.wikipedia.org. The “debate” makes for a fun storyline, but as the science shows, the real T. rex was even more impressive: a adaptable super-carnivore that ruled its ecosystem in life and in death.

T. rex’s legacy as the “Tyrant Lizard King” is well-earned – it was no wimp waiting for scraps, but a dynamic hunter and scavenger. This versatile feeding strategy likely contributed to its success as one of the last (and largest) dinosaurs before the end-Cretaceous extinction. Whether stalking live prey or sniffing out something dead, T. rex did it all, reminding us that nature’s top predators are rarely one-trick ponies. The king of the dinosaurs ate (and lived) on its own terms – and woe to anything, dead or alive, that stood in its way.

Stay Updated or Risk Falling Behind

Science is evolving rapidly—and in today’s chaotic information landscape, falling behind means losing ground to misinformation. This Week in Science delivers the most essential discoveries, controversies, and breakthroughs directly to your inbox every week—for free.

Designed for educators and science-savvy citizens, it’s your shield against bad data and outdated thinking.

Act now—subscribe today and stay ahead of the curve.

🔗 Liked this blog? Share it! Your referrals help defend truth and spread scientific insight when it matters most.