The Dead Internet Theory: Is Most of the Web Just Bots and Fake Content?

In corners of the internet, a troubling idea has been gaining traction: the “Dead Internet Theory.”

It’s a conspiracy theory claiming that the internet, as we know it, is essentially “dead” – that genuine human activity online has been largely supplanted by bots, AI-generated content, and carefully controlled narratives. According to this theory, the lively web of real people has been hollowed out, leaving behind a simulated shell dominated by artificial actors.

While the claim sounds far-fetched, it has struck a chord with many who feel that something about today’s internet is off. Is the internet really overrun by bots? Or is this theory an exaggerated symptom of our growing unease with an increasingly synthetic online world? This article examines the origins of the Dead Internet Theory, its core claims and purported evidence, the skeptics’ rebuttals, and its connection to broader anxieties about AI, digital media, and the future of online culture.

And hello! I’m Jon. A real person!

Origins of a Modern Internet Conspiracy

Like many grand conspiracy theories, the Dead Internet Theory emerged from online forums. Its exact origin is difficult to pinpoint, but a key moment occurred in early 2021. On a small forum called Agora Road’s Macintosh Café – a niche message board known for discussions of “lo-fi” internet culture and oddball conspiracies – a user with the handle “IlluminatiPirate” posted a manifesto titled “Dead Internet Theory: Most of the Internet is Fake.” This lengthy post presented the claim that the internet “died” sometime around 2016 or 2017, after which most supposedly human-generated content was allegedly produced by artificial intelligence and bots. The author asserted that what we see online today is largely a mirage: an internet empty of real people and flooded with automated content, sponsored influencers, and covert propaganda.

The Agora Road post by IlluminatiPirate didn’t come completely out of nowhere. By the author’s own account, it built upon earlier murmurings from anonymous users on platforms like 4chan’s paranormal board and a forum called Wizardchan. But this 2021 post became the “ur-text” of the Dead Internet Theory,the foundational text that took the idea beyond a few fringe imageboards and gave it a broader name and audience.

Over the following months, the theory spread to more mainstream forums and social media. Enthusiasts shared IlluminatiPirate’s manifesto across subreddits (including a Joe Rogan fan subreddit with hundreds of thousands of members) and tech discussion boards. YouTube creators jumped in with dramatic explainer videos; one Spanish-language summary garnered over a quarter of a million views. Even the notoriously skeptical Hacker News forum saw users speculate about whether the internet had secretly become overrun by bots. In short, a once-obscure notion leapt from the shadows of esoteric boards into wider internet culture.

Mainstream media took notice as well. In August 2021, The Atlantic published a widely read article titled “Maybe You Missed It, but the Internet ‘Died’ Five Years Ago”, bringing the Dead Internet Theory to a broader audience. The article’s author noted that while the theory itself is “patently ridiculous” in literal terms, it taps into real feelings of weirdness and déjà vu online. Other outlets, from tech magazines to science websites, followed with explainers attempting to dissect the phenomenon. By now, “Dead Internet Theory” has entered the lexicon as a piece of internet lore – often mentioned in the same breath as discussions about bots, fake news, and the creeping influence of AI on our digital lives. In other words, what began as an out-there conspiracy posting is now part of the conversation about what’s happening to the web.

Bots Everywhere: The Core Claims of Dead Internet Theory

At its heart, the Dead Internet Theory makes two sweeping claims about today’s online world:

Claim 1: Bots and AI have largely displaced humans online. Proponents argue that the majority of online content and activity is no longer generated by real people, but by artificial agents – bots, algorithms, and AI programs. According to the theory, everything from social media posts and news articles to forum discussions and product reviews may be authored by AI or “social bots,” not humans. These bots generate text, images, and even videos, often aided by algorithmic curation that enhances their visibility. The result is an internet where organic human expression is drowned out by what one commentator calls “AI slop” – an endless stream of auto-generated content optimized for clicks and virality rather than genuine communication. In the eyes of Dead Internet believers, this explains why so much online content feels repetitive or soulless: it’s literally machine-made.

Claim 2: A coordinated effort is behind the takeover – possibly for control and profit. The theory doesn’t stop at suggesting that bots are everywhere by coincidence. It posits a conspiratorial element, where powerful entities are deliberately controlling this bot-based internet. Government agencies, big corporations, or other shadowy actors are often fingered as the culprits pulling the strings. The alleged motive? To manipulate public opinion and consumer behavior at scale. By flooding the web with specific narratives or trends (and scrubbing away unapproved content), these actors can influence what people think, who they support, and what they buy. In IlluminatiPirate’s original post, this idea serves as the dramatic punchline – the “thesis” that follows the setup. “The U.S. government is engaging in an artificial intelligence-powered gaslighting of the entire world population,” the post declares bluntly. In other words, the theory claims a secret alliance of big tech and government has turned the internet into a giant Potemkin village: a facade of human chatter and culture, behind which lies a controlled simulation meant to keep the public docile and spending money.

Those are extraordinary claims, to be sure. Believers often pinpoint 2016 as the turning point – the moment the internet “died” and this bot takeover was complete. Why 2016? Some note that around this time, the internet’s character seemed to change. They cite the decline of old-school blogs and forums, the rise of algorithm-driven feeds on Facebook and Instagram, and the proliferation of misinformation bots during the 2016 U.S. election as signs that something fundamental has shifted. According to the theory, by 2016–2017, the organic, messy, human-driven web had been quietly replaced with a sanitized, monotonous stream of content controlled by AI and hidden hands.

Another key aspect of the theory involves search engines and content curation. Proponents argue that even our gateways to information, like Google, are part of the ruse. They claim that search results are heavily filtered and curated to show only a limited range of “approved” content, hiding vast swathes of information. They point to phenomena like “link rot” (when old links and web pages disappear over time) and suspiciously low numbers of relevant search results as evidence that the searchable web is much smaller – and more controlled – than we’re led to believe.

Some go so far as to suggest Google’s supposedly billions of search hits are a lie, masking a curated database akin to a Potemkin village of information. In the Dead Internet worldview, even the search index is curated to steer users toward certain narratives (and away from others), reinforcing the sense that we’re navigating a digital Truman Show where everything we see has been placed there intentionally.

Strange Evidence: Why Do People Believe It?

If the Dead Internet Theory sounds like a dystopian sci-fi plot or a creepypasta story, one might wonder how it has convinced anyone at all. Supporters, however, point to several types of “evidence” and observations that, in their view, back up the theory’s claims. Here are some of the key reasons proponents say “the internet is dead”:

Eerie Repetition of Content: One of the earliest observations that sparked this theory was the discovery of odd patterns and repetition online. Identical posts, comments, and threads keep appearing year after year, almost like deja vu. For example, a series of tweets that all begin with the phrase “I hate texting” followed by a romantic or lonely musing went viral on Twitter repeatedly, under different seemingly unrelated accounts. Each tweet was slightly varied (“i hate texting i just want to hold ur hand” … “i hate texting just come live with me” … “i hate texting i just wanna kiss u”), yet they popped up over and over, garnering tens of thousands of likes each time. To some observers, these cookie-cutter tweets looked less like genuine expressions from different individuals and more like the output of a content factory or bot network churning out relatable phrases for engagement. Forum users have similarly reported seeing the same images and memes, with the same accompanying text, circulate in cycles over the years. This uncanny recycling of content – beyond normal re-posts – feeds the suspicion that much of the internet’s “conversation” is just automated regurgitation.

Inflated Bot Traffic and Fake Accounts: While repetitive tweets are anecdotal, there is harder data that a significant chunk of internet activity comes from bots. Studies by cybersecurity firms show that bots (automated scripts or programs) account for a huge portion of web traffic. In fact, bots accounted for 52% of all web traffic as early as 2016, and that share has continued to grow in recent years. By 2022–2023, new analyses revealed that approximately half of all internet traffic is generated by non-human sources. That is an astonishing figure – effectively a 50/50 split between human clicks and automated requests on the web. Companies like Imperva, which track this, attribute the rising bot presence partly to generative AI tools crawling and scraping data, as well as the proliferation of malicious bots. For Dead Internet believers, such numbers are a smoking gun: if half the traffic online is bots, perhaps half the content and users are bots too. Indeed, on social platforms from Twitter to Facebook, fake accounts and bots often run rampant. Twitter (now X) has been notoriously plagued by bots – from spammers promoting cryptocurrency scams and pornography to politicized bot networks amplifying specific hashtags. Even Elon Musk, Twitter’s owner, admitted that automated accounts are such a problem that the platform might need to charge every user a fee to weed out the bots. On Facebook, strange surges of obviously AI-generated profiles and comments have been observed. For instance, in 2024, Facebook users saw nonsense AI-generated images, known as “AI slop,” such as the bizarre “Shrimp Jesus” meme, receive thousands of comments, including “Amen!” from what appeared to be fake accounts. To theorists, these are signs that the internet’s crowd is increasingly an illusion – a hall of mirrors filled with fake personas.

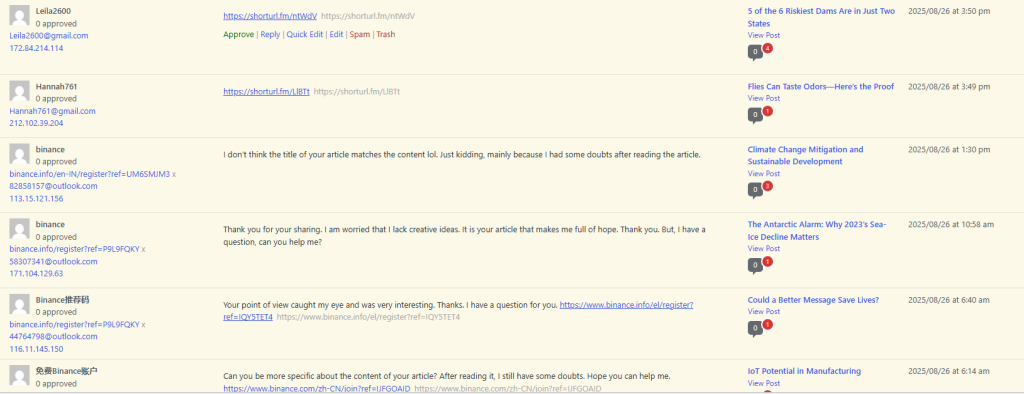

Take a look at our comment section! Thank you spam filters!

Astroturfing and Algorithmic Amplification: Another pillar of evidence is the ease with which engagement metrics and trends can be faked or manipulated. It’s well-documented that likes, follows, and views can be purchased through click farms or bots at a low price. Major platforms have had scandals revealing that their engagement numbers were grossly inflated or gamed. For example, Facebook acknowledged in 2018 that it had overestimated video viewership metrics by up to 900%, partly due to counting methods that ultimately misrepresented genuine user interest. YouTube engineers, around the same time, grew concerned about a scenario they dubbed “the Inversion” – a hypothetical tipping point where so much of the view counts and traffic came from bots that the algorithm might mistake bot behavior for authentic user behavior. In fact, fake views were so rampant on YouTube for a period that engineers feared their detection system could start flagging real views as fake, and vice versa. Proponents of the Dead Internet Theory seize on these incidents, arguing that they indicate the default state of the internet has become artificial. If bots can fool even Big Tech’s own systems, who’s to say how much of what seems popular online is actually just a mirage of coordinated inauthentic activity? A viral meme, a trending hashtag, a flood of product reviews – any or all of these could be orchestrated or auto-generated. The theory takes these real problems of astroturfing (fake grassroots activity) and extrapolates them to an extreme conclusion: that most online discourse is essentially staged or simulated.

Quality of Content and “AI Feel”: Some of the “evidence” is subjective but resonates with people’s gut feelings. Many internet users have noticed that online content has become increasingly formulaic, shallow, or spammy in recent years. Search for a product or health advice, and you’ll encounter dozens of websites that read like they were “created for search engines instead of people,” as Google itself put it in 2023. These sites are often laden with keywords and generic text, giving the sense that an algorithm – not a thoughtful person – assembled them. Google has acknowledged that the web is being inundated by AI-generated or AI-optimized pages that “feel like they were created for search engines” and has begun adjusting its algorithms to demote this low-value content. Furthermore, the rise of AI writing tools has meant we now regularly stumble upon content that has that indistinct, sometimes off-kilter tone of machine-generated text. When every other blog post or news item reads like bland, homogenized boilerplate, it’s easy to wonder: was this written by a human or a bot? Proponents argue that this dehumanization of content isn’t just our imagination – it’s the result of AI flooding the zone. They also note phenomena such as deepfakes and AI-generated media, which blur the lines between reality and fiction. The existence of convincing deepfake videos and synthetic photos (faces of people who don’t exist, etc.) means anything could be fabricated online. If a realistic video of a world leader can be faked, then how can we trust that the person we’re chatting with on a forum is real? In the conspiracy narrative, these technological developments are all pieces of a puzzle, suggesting an internet where illusion has overtaken reality.

Straight from the Source – Tech Predictions: Interestingly, some evidence cited by Dead Internet theorists comes from the tech community itself. AI researchers and futurists have warned about the very scenario the theory describes. In 2022, for instance, a researcher at the Copenhagen Institute for Futures Studies, Timothy Shoup, speculated (at the time) that if an advanced language model like GPT-3 were allowed to generate content, “the internet would be completely unrecognizable.” He predicted that by the mid-2020s, 99% of online content could be generated by AI in such a scenario. This wasn’t a conspiracy theorist speaking, but an expert commenting on the trajectory of generative AI. Such statements are seized by believers as validation: experts themselves say the internet could soon be nearly all AI content.

Likewise, the fact that OpenAI’s ChatGPT exploded onto the scene in late 2022 gave credence to the theory’s general premise. All of a sudden, millions of regular people had access to AI that could write blogs, social media posts, even scripts and code. Journalists noted that the Dead Internet Theory felt “more realistic than before” once ChatGPT arrived, precisely because it became easy to imagine ordinary users (not just state actors) flooding forums with AI-written material. In short, the world is now catching up to the idea that a huge portion of internet content could be machine-made – lending a bit of legitimacy (or at least understandable anxiety) to what was earlier a fringe idea.

To sum up, the evidence proponents marshal ranges from hard statistics (half of web traffic is bots) to anecdotal oddities (carbon-copy tweets and meme déjà vu) to the general feeling that “everything online seems fake nowadays.” Individually, these data points have logical explanations: Yes, bots are common (some are search engine spiders or harmless tools, others are spam – but either way that doesn’t mean humans are gone). Yes, clickbait and SEO-driven content are rampant because there’s profit in it, not necessarily because of an overarching government plot. But to someone steeped in Dead Internet forums, all these signs knit together into a grand narrative: an internet that is largely an automated illusion.

Skeptics Speak Up: A Reality Check

While the Dead Internet Theory has passionate adherents, it faces plenty of criticism and skepticism – and not just from Silicon Valley execs, but also from journalists, academics, and everyday internet users who see a more nuanced reality. Here are some key counterpoints raised by skeptics of the theory:

“The Internet is not literally a government psyop.” Even those who find nuggets of truth in the theory are quick to reject its most extreme, coordinated-conspiracy aspect. As The Atlantic’s Kaitlyn Tiffany put it bluntly, “Obviously, the internet is not a government psyop.” There is no public evidence that the U.S. government (or any other government) secretly replaced the majority of the internet with bots in 2016. That notion is generally regarded as paranoid fantasy. Caroline Busta, a media analyst who has talked about the theory, agrees that much of the IlluminatiPirate manifesto reads like “paranoid fantasy” – though she noted the overarching idea of an increasingly synthetic internet struck a chord. In reality, while governments have used bots and troll farms to attempt influence operations on social media, these efforts don’t amount to wiping out human presence online. Instead, they are tactical, targeted campaigns – for example, Russia’s notorious bot-driven disinformation during the 2016 election, or China’s use of bots to sway opinions on global platforms. These are serious concerns, but they are a far cry from the theory’s claim that the entire internet has been commandeered. Think of it this way: Yes, there are lots of “fake” accounts and posts, but there are also billions of genuine users posting selfies, cat videos, personal stories, and memes every second. The internet is cacophonous; it has bots and humans – not one or the other.

Misidentifying the Villain: Critics also point out that the theory’s focus on a single grand actor (like the U.S. government) may be misplaced. The true drivers of bot proliferation might be more mundane: spammers, scammers, marketing firms, or propagandists of various stripes, each acting in their own interest. It might indeed be “sinister,” but not in the singular, centralized way the theory imagines. A recent analysis by researchers noted that social media is manipulated by “inflated bots to sway public opinion” and has been for years. However, this manipulation often comes from various sources: political groups, profit-seekers, and malicious actors capitalizing on algorithms. For instance, studies found that bots were significantly involved in spreading disinformation during major events like the 2016 election and even after tragedies (amplifying divisive narratives after mass shootings). These bot networks are real, but attributing them all to one government master plan is speculative. In other words, the internet may feel “fake” at times, not because a puppet-master made it so, but because anyone with enough bots or fake accounts can temporarily manufacture trends or consensus. That’s a problem, but it’s a decentralized, chaotic one – arguably harder to solve, but also not as neat as a single switch being flipped to “kill” the internet.

Humans Still in the Loop: Another counterargument is simply the persistence of real human activity that anyone can observe online. If the internet truly “died” in 2016, how does one explain the countless authentic interactions that clearly do happen every day? Skeptics invite people to consider their own online life: Have you not chatted with old classmates on Facebook, learned a craft from a niche YouTuber, laughed at a friend’s genuine joke on Twitter (X), or participated in a hobby forum with knowledgeable enthusiasts? These aren’t bots – they’re people. The Dead Internet Theory tends to dismiss personal observations as naive (suggesting maybe even your friends’ posts are bots spoofing them), but that veers into unfalsifiable territory. The more straightforward explanation is that both authentic and fake content coexist, with the balance varying by platform and context. For example, platforms like Instagram may be heavy on curated, influencer content (some of which is arguably staged or promotional), whereas platforms like LinkedIn often see legions of bots posting spam job ads. However, in numerous corners ( a neighborhood Facebook group, a private Discord server, an academic mailing list ) the conversations remain distinctly human. Critics argue that proclaiming the whole internet “dead” ignores these genuine communities and the very real people behind them. It’s painting with far too broad a brush. The internet has undoubtedly changed since its early days, becoming more commercialized and algorithmically driven – but change is not the same as wholesale extinction of humanity online.

No Sharp Drop-off in 2016: The choice of 2016 as the alleged death date also draws skepticism. Why that year exactly? Believers cite some reasons (as mentioned, the election bots, a feeling of homogenization starting then, etc.), but there’s no empirical evidence of a sudden collapse in human online activity around 2016. If anything, the number of internet users worldwide has continued to grow year after year through the 2010s and beyond. Billions of people came online for the first time during that period, especially via smartphones and the expansion of connectivity in developing countries. Human participation was booming, not dwindling. What did happen around 2016 was that AI and bot technology made noticeable leaps (for instance, early generative models, more sophisticated social media bots), and the big platforms doubled down on algorithmic feeds, which tend to promote viral content. So the character of online content shifted, perhaps becoming more echoey and repetitive. But it wasn’t because millions of humans vanished – rather, a relatively small number of automated systems and content farms simply got better at injecting content into our feeds. Skeptics view the Dead Internet Theory as conflating correlation with causation, or mistaking the noise (the prevalence of bots and spam) for the signal (the continued presence of real humans). Yes, the ratio of signal-to-noise online may have worsened, but the signal (actual human voices) is still there if you know how to listen.

Experts: From Fantasy to “Kernel of Truth”: Tech writers and internet historians who have examined the theory tend to conclude that it’s a mix of insightful and absurd. Robert Mariani, writing in The New Atlantis, described Dead Internet Theory as part genuine critique and part “creepypasta” (an internet horror story). It’s evocative as a metaphor but not literally true. The metaphor – that the internet’s vibrant “living” culture has been drained – resonates with people who remember the quirkier, community-driven web of the past. Many netizens feel nostalgic for the days of personal blogs, independent forums, and chaotic originality that seem harder to find now amid the polished social media feeds. Even Facebook’s own employees have said they miss the “old internet” that felt more alive and less algorithmically engineered. So when the theory says the internet is “dead,” some interpret it more loosely: not that humans are gone, but that the spirit of the early internet has died, replaced by the equivalent of a strip mall filled with bots and brands.

This broader lament strikes a chord, and even cynics of the literal conspiracy acknowledge the feeling. Kaitlyn Tiffany noted that the Dead Internet people “kind of have a point” in that “everything that once seemed real now seems slightly fake.” We are inundated with sponsored posts and AI-crafted smoothness, which can make the internet experience feel sterile. However, Tiffany and others caution against falling into all-or-nothing thinking. There are legitimate issues like bot traffic, fake engagement, algorithmic echo chambers, but addressing those doesn’t require believing that “all influencers are government agents” or that “no one on Twitter is a real person.”

In essence, the consensus outside the conspiracy circles is that the Dead Internet Theory is an exaggeration built on real concerns. Yes, bots and AI content are on the rise; no, human life online is not extinct. It’s worth separating the fact from the fiction: There is ample evidence of widespread bot activity and curated content online, yet the “full theory” that the internet is mostly fake is not supported by evidence. The truth is messier – the internet has both vibrant life and creeping “undead” elements coexisting.

The Age of AI: Why the Theory Feels Timely

Even if the Dead Internet Theory is a conspiracy theory, it didn’t arise in a vacuum. Its popularity reflects real anxieties about the trajectory of technology and media. In particular, the recent explosion of generative AI and synthetic media has made the theory feel uncannily relevant – almost as if reality is catching up to its wild claims.

Consider the landscape from 2023 to 2025: AI systems can now generate text, images, audio, and video that are increasingly indistinguishable from human-created content. We have AI chatbots that can carry on conversations and write entire articles or social media posts on demand. We have image generators that produce artwork or photorealistic pictures with a simple prompt. We even have AI tools that can mimic voices or create deepfake videos of people saying things they never said.

This rapid progress raises an unsettling question: Are we heading toward an internet where a significant portion of content is actually machine-generated?

Signs of this shift are already visible. In late 2022, when OpenAI released ChatGPT to the public, there was immediate speculation about its impact on the web. Suddenly, anyone could use AI to write plausible product reviews, comments, blog posts, even entire websites. Journalists warned that the internet could soon be swamped with AI-generated text that “drowns out organic human content”, aligning with the very scenario Dead Internet theorists described. Within months, reports emerged of “AI-generated blogs” and spam sites designed solely to game Google search rankings. Google’s own quality team noted a surge of auto-generated sites “created for search engines” rather than human readers, acknowledging that generative AI was fueling this rapid proliferation. The company has since been in a cat-and-mouse game to down-rank what some call “SEO spam” or “AI-written slop,” but the sheer volume is daunting.

On social media, 2023 and 2024 witnessed bizarre trends, including the aforementioned “Shrimp Jesus” on Facebook – a quirky AI-generated meme (images of Jesus merged with a shrimp or crustacean) that went viral, garnering huge engagement. The kicker: much of that engagement itself was from AI-driven accounts, creating a surreal loop of bots consuming content made by bots. Observers described it as a “vicious cycle of artificial engagement” that involved humans to a minimal extent. What starts as a harmless parody can morph into a disturbing proof-of-concept: an internet moment where humans were almost an afterthought.

This relates to broader issues surrounding synthetic media. Deepfakes and algorithmically generated videos mean that not only text, but also audiovisual content, can be faked en masse. Europol (the EU’s law enforcement agency) has warned that AI-generated media could allow bad actors to “misrepresent events or distort the truth” in a convincing manner. If we can no longer trust our online eyes and ears, the implications for propaganda and misinformation are dire. The Dead Internet Theory taps into this fear by suggesting such manipulation isn’t just possible, but already ubiquitous.

Another facet is the algorithmic curation issue: the concern that what we see online is heavily filtered by algorithms tailored to maximize engagement (and profit), rather than to show an authentic picture. This isn’t a conspiracy; it’s how social media and even search engines largely operate. If those algorithms also start favoring AI-generated content (which is cheap and abundant), it could further marginalize genuine human posts.

There’s an emerging feedback loop concern: AI content is flooding the internet, which is then used to train new AI, which in turn produces even more synthetic content. Researchers have noted that training AI on data that increasingly contains AI-generated text could degrade quality and create “a loop of unreality.”

In the context of something like Reddit, as more users (or bots) deploy AI to generate comments or answers, the site’s overall content could lose the personal touch that made it useful, leading to a kind of death by automation. In mid-2023, Reddit actually faced a moderation crisis where volunteer moderators worried that bots and AI would overwhelm their communities after the site began charging for API access (which affected moderation tools and third-party apps). Some academics even explicitly drew parallels to the Dead Internet Theory when discussing the prospect of Reddit being flooded with AI-generated posts and bots.

Beyond the content itself, AI “agents” are now poised to become online actors in their own right. Tech companies have floated the idea of deploying AI personas on social networks. For instance, Meta (Facebook’s parent company) announced plans in 2024 to introduce AI-powered autonomous accounts on its platforms – complete with profile pictures and the ability to post and interact like any user. Meta envisions these AI agents as helpful or entertaining, but critics reacted with a Dead Internet Theory vibe: Are we really going to populate our social networks with pretend people? Meta’s VP of generative AI, in describing these forthcoming bots, said they will exist “in the same way that accounts do” and will mingle with human content. To skeptics, this sounds like officially inviting bots into the mix of our digital public square – a slippery slope toward normalizing non-human participants in what used to be human conversations.

All of these developments give the Dead Internet Theory a new life (no pun intended) in public discourse. In 2018 or 2019, the idea that “most of the internet is AI” was easy to dismiss outright. By 2025, we’ve seen enough AI-driven content and bot activity that the theory feels uncomfortably closer to reality, at least in part. Importantly, you don’t have to believe in any grand conspiracy to worry about an internet overrun with fakeness – accidental or profit-driven overrun is scary enough. As one tech journalist quipped, the Dead Internet Theory is “ridiculous, but possibly not that ridiculous?”.

In connecting the theory to our AI-infused world, it raises larger questions: How will we preserve authentic human voices online?

Do we need better labels or detection for AI content? Should platforms allow or ban AI-generated posts from bots masquerading as people? And how do we maintain trust in what we see and read, when we know a convincing fake can be mass-produced at scale? These are questions society is grappling with, regardless of the conspiracy theories circulating.

Digital Culture, Trust, and the Future of Online Communities

Beyond the technical aspects, the Dead Internet Theory strikes a chord regarding digital culture and trust. What does it mean for us – the users, communities, and citizens of the internet – if the online world is perceived as increasingly “fake”? Even if one rejects the literal theory, the undercurrents of truth in it force us to confront some challenging implications:

Erosion of Trust: One obvious effect of the idea that “anyone you encounter online might be a bot” is a deepening mistrust in online interactions. People have already grown cautious about anonymous strangers on the internet; if we add the possibility that the stranger might not even be human, it’s a recipe for cynicism. Trust is the currency of online communities – whether it’s trusting that the product review you’re reading is a genuine customer opinion and not paid-for propaganda, or trusting that the person you’re debating on Twitter is arguing in good faith and not some troll farm sockpuppet. If that trust collapses, online discourse could become even more fractured and hostile. We may start dismissing any viewpoint we dislike as “probably a bot,” which shuts down meaningful conversation. In fact, this is already observable: In heated debates on social media, it’s not uncommon to see someone retort, “Nice try, bot,” to an opponent, effectively accusing them of being a paid shill or automated account. The Dead Internet Theory, by popularizing the notion that bots dominate, might inadvertently encourage people to write off others too readily. If everyone assumes the worst (that the internet is full of fake people), genuine connections suffer.

Psychological Impact on Users: Being surrounded by what you feel are non-human or inauthentic interactions can be alienating. There’s a term that some have used – “feeling dead inside” – to describe the emotional toll of an internet that doesn’t feel alive with human touch. For example, consider an online support group for patients with a certain illness. If those seeking support start suspecting that the helpful posts or empathetic replies they receive might have been auto-generated by an AI (perhaps deployed by the site or a well-meaning project), it could be deeply disheartening. In one extreme case, an academic article noted the psychological impact on cancer patients who discovered that some “people” giving them support in forums were actually chatbot assistants – it made them feel deceived and more isolated. While that’s a specific scenario, it underscores a general principle: we derive comfort and meaning from knowing there are real humans on the other end of the line. Remove that certainty, and online interactions can start to feel hollow.

The Diminishing of Authentic Communities: An internet dominated by bots and AI content would also jeopardize the very concept of online community. Many of us have found tribes and friendships on the web – niche forums for our hobbies, subreddit groups for personal challenges, social media circles of like-minded folks. These communities thrive on human quirks, personal stories, and the spontaneous ebb and flow of conversation. If overrun by automated content, those spaces risk losing their charm and utility. Imagine a discussion thread where half the posts are just AI-generated filler or clickbait links; real users might disengage, leading to a self-fulfilling outcome where the community actually dies. This concern is why Reddit’s changes in 2023 (which made it harder for moderators to use tools to manage bots) caused such an outcry – moderators feared an “AI spam flood” would ruin their communities. In essence, the health of online communities depends on keeping human-to-human interaction at the core. The Dead Internet Theory, even if exaggerated, is a cautionary tale of what could happen if we fail to do so.

Public Discourse and Democracy: Zooming out, there’s a societal dimension. The internet is today’s public square. If that public square is teeming with fake people shouting propaganda or algorithms amplifying outrage bait, the consequences for democracy and public discourse are serious. We already saw glimpses of this with election interference via bots. The theory’s claim of “government or industry-controlled narratives” speaks to a real fear: that what trends on social media or what stories gain prominence can be orchestrated by those with resources, drowning out organic grassroots voices. If citizens lose confidence that what they see online reflects genuine public opinion, it can breed disengagement or extremism. For instance, someone might falsely believe “everyone is against X policy, I see it everywhere on social media,” not realizing it’s a manufactured campaign – leading them to question whether their own stance is an outlier or to feel helpless against a seemingly unanimous crowd. On the flip side, awareness that bots are in play can make people appropriately skeptical, but if taken too far it can also feed into conspiracy thinking (where any opposing view is attributed to nefarious bots, as mentioned). Society will have to find a balance between healthy skepticism and paranoia in navigating digital discourse.

“We Become Bots Ourselves”: A provocative point that some commentators have raised is the notion that as the internet becomes more algorithm-driven, human users might start behaving in more bot-like ways. What does that mean? Essentially, when our feeds incentivize certain reactions – quick likes, shareable one-liners, rage clicks – we can fall into patterns of reacting automatically, without nuance, almost as if we are following a script. The Dead Internet Theory ironically mirrors this by describing humans acting “predictably” and “on impulse” to manufactured content. Charlie Warzel, a journalist, has written about how social media’s design leads to “context collapse,” where random trivial topics blow up into massive trends with everyone piling on, in a way that feels orchestrated. He suggests that many of these dogpile trends are essentially engineered, and users perform their outrage or commentary like actors hitting their cues. In a sense, even with no bots involved, people can start to feel like NPCs (non-player characters) in a game – each playing a role in repetitive online dramas. This blurring line between genuine human reaction and conditioned response is yet another angle of the “dead internet” anxiety: the fear that authenticity is being leached out of our online behavior, not just content. It’s a bit philosophical, but worth pondering: if the environment is saturated with algorithmic influence, do we unconsciously adapt and lose some of the spontaneity that marks human interaction?

In light of all this, what might the future hold? The concerns raised by the Dead Internet Theory – even after stripping away exaggeration – suggest a need for action and adaptation. Tech platforms are starting to respond, at least superficially. Twitter (X) is looking at paywalls and verification steps to deter bots. Companies like OpenAI and Google are researching ways to watermark or identify AI-generated content, so that it can be labeled or filtered. Regulators and lawmakers are also increasingly interested in addressing bot-driven disinformation and requiring transparency in online content. For example, there are calls in some countries for mandatory labeling of deepfakes or AI-generated political ads. Whether these efforts will keep pace with the proliferation of generative AI is an open question.

At the individual level, digital literacy is crucial. The UNSW analysis, republished by The Conversation, concluded that while the Dead Internet Theory isn’t literally saying all your interactions are fake, it serves as a useful lens to remind us to stay skeptical and critical online. We should question what we see – especially viral crazes or extreme consensus that appears out of nowhere – and ask, “Could this be synthetic or manipulated?” Without sliding into total paranoia, maintaining that critical eye can help preserve the integrity of our online experiences. It’s a bit like living in a world with mannequins among people; you learn to tap a few to see which are real, but you don’t assume everyone is a mannequin.

Finally, there’s a hopeful note: The very fact that people worry about the internet feeling “dead” means they value it being “alive.” In other words, we cherish the internet as a space for genuine human connection, creativity, and discourse. The nostalgia for the old internet and the alarm at a bot-filled one both stem from a desire for an online world that is authentic and enriching. That suggests users might gravitate towards solutions – new platforms, community verification methods, AI filters – that foster realness. For instance, smaller curated communities (like private group chats, invitation-only forums, etc.) could become havens of human interaction in an AI-noisy world. The internet might splinter somewhat, with pockets of “verified human” spaces separated from the wild public feeds.

A Web of Reality and Illusion

So, is the internet “dead” or alive? The truth is, it’s neither and both. The Dead Internet Theory wraps a core of genuine issues in a shell of conspiracy. It is not true that the internet has been wholly taken over by bots and that human voices have vanished – scroll through any heartfelt personal blog or watch a niche YouTube creator and you’ll see the spark of real human presence. However, it is true that the internet of 2025 is deeply intertwined with artificial activity. Bots and AI-generated content are regular parts of the online ecosystem now, sometimes lurking in the shadows, sometimes operating out in the open. Much of what we encounter on big platforms each day – from trending topics to the comments under a news article – may be influenced or even dominated by inauthentic actors. That doesn’t mean organic human content is gone; it means it competes in a crowded arena filled with clever simulations.

The Dead Internet Theory resonates because, at a gut level, many of us sense a loss of authenticity as the web has matured. The internet isn’t “dead,” but a certain ideal of it – a purely human-driven cyberspace – may be dying. In its place is a hybrid: part human, part machine, frequently manipulated, yet still capable of genuine connection. The task ahead for all of us is learning how to thrive in this hybrid environment. We must learn to detect and disempower malicious bots, support and amplify real voices, and demand transparency from platforms about what is real versus automated. It’s a new kind of literacy for a new digital era.

In the end, perhaps the best antidote to the gloom of the Dead Internet Theory is to prove it wrong by seeking out life online. As Kaitlyn Tiffany wryly noted, the very existence of a weird forum rant about the internet being dead was, paradoxically, evidence that the internet is alive – because a bot likely wouldn’t have written such a passionate, absurd, and distinctly human screed. The internet is what we make of it. If we fill it with our creativity, humor, empathy, and critical thinking, those human elements will shine through the haze of bots. The web’s future is not set in stone; it could become a sterile playground of AI, or it could remain a vibrant tapestry of human voices (with some robot assistants on the side). More likely, it will be a bit of both.

The Dead Internet Theory gives us a chilling picture of one extreme. It challenges us to ask: How do we keep the internet “alive” with humanity? Answering that question is an ongoing project – one that will define the digital culture and public discourse of tomorrow. In the meantime, stay curious, stay skeptical, and don’t be afraid to “poke” the internet to see if it bleeds (metaphorically speaking). There’s still plenty of real pulse out there behind the pixels, if you know where to look.