Flies Can Taste Odors—Here’s the Proof

If you’ve ever walked past a bakery and suddenly needed a pastry, you know how powerful smell can be in jump-starting hunger. But what if I told you that in fruit flies, smell doesn’t just tickle the nose—it actually activates their taste buds?

That’s the wild takeaway from a new study on Drosophila melanogaster (our favorite tiny lab fly) that rewrites what we thought we knew about how animals sense and decide to eat.

The Taste Buds That Sniff

In humans and most animals, smell and taste have their own clearly marked jobs. Smell detects volatile chemicals in the air, taste detects chemicals we put in our mouths. They team up in the brain to create the rich flavor experience we know and love.

But researchers at eLife found something unexpected: in flies, odor molecules can directly trigger taste neurons—the ones that usually fire only when sugar hits the tongue-like mouthparts. These neurons then spark the proboscis extension reflex (PER), which is basically a fly saying, “Yes please, I’ll have some!” and reaching out its straw-like mouth for food.

And here’s the kicker: this odor-triggered taste reaction happens even when the fly’s traditional smell organs are removed.

How They Figured It Out

The team set up a delicate experiment with individual tethered flies, delivering different odors while tracking tiny mouthpart movements with deep-learning motion capture.

Normally, PER happens when a sweet liquid touches the taste receptors on a fly’s legs or proboscis. But in this setup, no sugar was offered—just the scent of things like banana, ethyl butyrate, or 4-methylcyclohexanol. To their surprise, the flies still extended their proboscis, and not just once, but repeatedly.

Even more surprising: the “sweet taste” neurons themselves lit up in calcium imaging scans when exposed to odors. That’s like your tongue suddenly deciding it can detect the smell of fresh bread without needing your nose.

Sweet vs. Bitter: A Tiny Tug-of-War

Not all taste neurons agreed on whether odor should trigger feeding. Flies have sweet-sensing neurons (Gr5a) that promote PER, and bitter-sensing neurons (Gr66a) that put the brakes on it.

The study showed that sweet neurons were the main drivers of odor-induced PER, while bitter neurons tried to suppress it—especially in flies that weren’t hungry. Knocking out the sweet receptor Gr5a almost completely erased the odor response, proving it’s essential for the effect.

Smell-Taste Fusion Right at the Source

One of the biggest surprises here is where this integration happens. We tend to think of multisensory blending as a “brain thing”—two separate inputs meeting in the central nervous system. But in flies, this fusion is happening at the very first stage, in the gustatory receptor neurons themselves.

That means the decision to start eating can be influenced before the brain even gets the full sensory report.

And this integration isn’t just academic—it has real feeding consequences. When the researchers paired a faint banana odor with a weak sugar solution, flies were far more likely to initiate feeding and ended up eating more, even without their smell organs.

Why Would Evolution Do This?

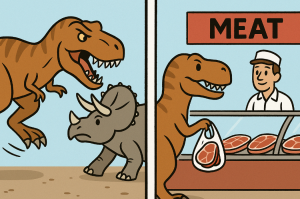

From a fly’s-eye view, it makes perfect sense. In the wild, odors signal the presence of food. If you’ve already landed somewhere that smells like overripe fruit, odds are it’s edible. Having taste neurons that are “primed” by smell gives you a quicker, more decisive start on eating before a competitor gets there.

It’s like walking into a kitchen where someone’s just baked cookies—your hand is already halfway to the jar before you consciously decide to grab one.

Could This Apply Beyond Flies?

The researchers point out that odor receptors in taste structures aren’t unique to flies. Other insects show similar setups, and in mammals—including humans—some taste bud cells appear to have olfactory receptors too. That means our own taste buds may be doing more than we think when we catch a whiff of dinner cooking.

If that’s true, this peripheral blending of smell and taste could be a widespread biological shortcut for deciding when and what to eat. It might even explain why certain smells can make our mouths water instantly, no thought required.

A Shift in How We Think About the Senses

This work challenges the neat boundary lines we’ve drawn between the senses. Smell and taste don’t just meet in the brain—they can overlap in the same neuron, changing the first step of how animals detect and evaluate food.

It also raises some big questions. Could other “separate” senses be doing the same? Do temperature-sensitive touch receptors also respond to smells? How does this kind of sensory mash-up affect behavior in the real world?

One thing is certain: next time you smell banana bread, remember that somewhere in your sensory system, there might be a little shortcut convincing you it tastes just as good as it smells—before you’ve even taken a bite.

Let’s Explore Together

This study makes me wonder how many other hidden sensory connections are quietly shaping what and how we eat.

How do you see this research affecting your life?

What would you do with this discovery—design better flavor experiences? Control appetite?

What’s the coolest science fact you’ve learned recently?

Drop your thoughts in the comments or share this with your fellow science fans. Who knows—someone you know might be about to have their mind blown by a fruit fly.