Ancient Engravings 250,000 Years Older Than You Think

In the pitch-black depths of a South African cave, 30 meters underground and far from daylight, a mystery was carved into stone—long before our own species even existed.

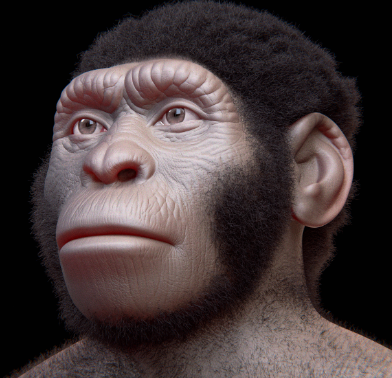

The year is not 2023 but somewhere between 241,000 and 335,000 years ago. The artist? Almost certainly not Homo sapiens. Instead, the likely creator was Homo naledi, a human cousin with a brain roughly one-third the size of ours. Until recently, scientists believed only big-brained species like us—or maybe the Neanderthals—could make intentional, abstract designs. This discovery could change that story forever.

A Hashtag Before Hashtags

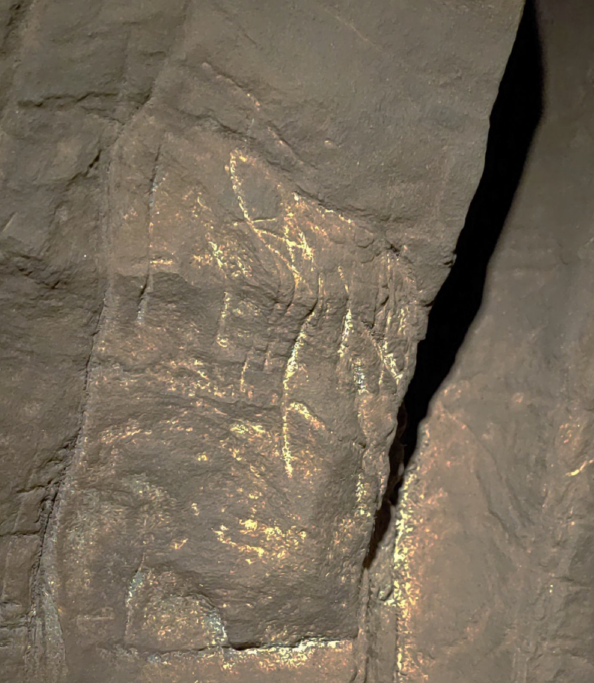

The engravings were found in the Rising Star Cave system, in a section known as the Dinaledi Subsystem. On a natural stone pillar, researchers spotted deliberate markings: cross-hatchings, lines forming shapes like squares, triangles, and X’s. If you squint, one of them even resembles a hashtag, though this one predates Twitter by hundreds of millennia.

The lines weren’t random scratches. They were carved with care, using a tool hard enough to bite into dolomitic limestone. Some lines clearly cross over others, showing a sequence in their creation. In places, the surface appears to have been smoothed beforehand—possibly to make the engravings stand out. There’s even residue that may have been applied intentionally, perhaps as a pigment or polish.

And here’s the kicker: these engravings are located in a place that Homo naledi would have passed while traveling between two chambers used for burials. That suggests they may have held meaning—whether symbolic, ritual, or simply communicative.

The Unlikely Artist

Homo naledi was first described in 2015, after more than 1,500 fossils were recovered from the same cave system. They were short, with curved fingers, small teeth, and a brain about the size of an orange. For decades, scientists thought such a small brain meant limited cognitive abilities. But Homo naledi has already surprised us—there’s evidence they deliberately buried their dead, an act once thought uniquely human.

If these engravings really are their handiwork, it would mean that complex, abstract thinking didn’t require a big brain after all. The evolutionary timeline for symbolic behavior would stretch back far earlier than most scientists imagined.

Hold the Champagne—For Now

Here’s where things get tricky. The engravings haven’t been directly dated. That means the only reason to link them to Homo naledi is the fact that their fossils—and no other hominin remains—have been found in this part of the cave. The team argues that modern humans haven’t altered the cave walls in the 40 or so years since cavers first entered, but skeptics say this isn’t airtight proof.

Some researchers also question whether the marks are truly artificial. Dolomite, the rock in question, can develop natural grooves from erosion or fracturing. However, the team points out several features that set these lines apart: their shallow depth, their composition from repeated tool strokes, their patterning into geometric shapes, and their occasional crossing over fossilized stromatolites in the rock.

Still, without dating the markings—or finding a Homo naledi tool with matching wear marks—the debate is far from settled.

Why This Matters

If these engravings were indeed intentional, they join a growing list of discoveries showing that humans aren’t the only species capable of symbolic thought. Neanderthals in Gibraltar made similar cross-hatched engravings around 60,000 years ago. At Blombos Cave in South Africa, early Homo sapiens etched geometric patterns into ochre about 73,000 years ago. Even Homo erectus may have engraved a zigzag pattern on a shell more than 400,000 years ago.

The Dinaledi engravings would blow all these examples out of the water, both in age and in the unexpected identity of the artist. It would suggest that symbolic behavior might have evolved multiple times in different human lineages, or that it emerged far earlier than our current evidence shows.

It would also force us to rethink how intelligence is measured. If a small-brained hominin could create and perhaps even share symbolic designs, then brain size alone isn’t the whole story.

A Glimpse into the Dark

Picture the scene: deep in a twisting cave system, far beyond the reach of daylight, Homo naledi individuals gather near a smooth stone pillar. In flickering firelight, someone picks up a sharp stone and begins to carve, pressing firmly, stroke after stroke, until a cross-hatch pattern emerges. Others pass by in the days, years, or even centuries that follow—adding new lines, touching the surface, perhaps telling stories about what the marks mean.

We may never know exactly what they were trying to say. Were these territorial markers? Ritual symbols? Simple doodles to pass the time? Whatever their purpose, they speak across a gulf of time, reminding us that creativity is a deep part of our shared family tree.

What Happens Next

The research team plans to conduct further analyses—sampling residues, mapping every mark in detail, and experimenting with carving techniques on similar rock. Direct dating will be key to confirming the age, and use-wear studies could reveal what kind of tool made the lines.

In the meantime, the Dinaledi engravings stand as an open invitation to rethink human history. They could be the world’s oldest known intentional designs—or a natural puzzle masquerading as art. Either way, they’ve already sparked a conversation that stretches from the scientific community to anyone curious about where we come from.

Let’s Explore Together

What do you think these engravings meant?

If a small-brained human cousin made art, how does that change your view of intelligence?

What’s the oldest or strangest artifact you’ve ever seen in a museum?

Share your thoughts in the comments, or pass this story along to a friend who loves a good archaeological mystery.