What Really Happened to South America’s Giants?

Twelve thousand years ago, giant ground sloths the size of cars, horse-like creatures with long skulls, and armored armadillos as big as Volkswagens roamed the plains of South America. Yet within just a few centuries, they were gone. For decades, scientists argued: was it climate change—or was it us? A new study from South America has just tipped the scales, and the answer places humans squarely in the center of the story.

From Myth to Science

Long before radiocarbon dating, Andean myths told of colossal beasts that once walked the earth. Some even said the land itself swallowed them up. Modern archaeology paints a different picture: these animals didn’t vanish quietly. They were hunted, systematically, and far more heavily than we thought.

In fact, researchers now show that extinct megafauna—mammals weighing over 44 kilograms—were not a side dish in ancient diets. They were the main course. This upends a long-standing belief that giant creatures were only a “marginal” resource for early South American foragers.

The Puzzle of Extinction

Scientists have wrestled with the “Pleistocene extinction” puzzle for decades. In North America, the debate is fierce: some argue warming climates pushed species beyond their limits, while others say spear-wielding humans were the decisive factor. In South America, most assumed climate mattered more. Humans, it was thought, simply arrived too late and had too little impact.

But the new study flips this. By separating archaeological sites into pre-extinction (before 11,600 years ago) and post-extinction layers, researchers avoided a key error: lumping together bones from very different time periods. Once they untangled the timelines, a striking pattern emerged.

A Hunting Economy Built on Giants

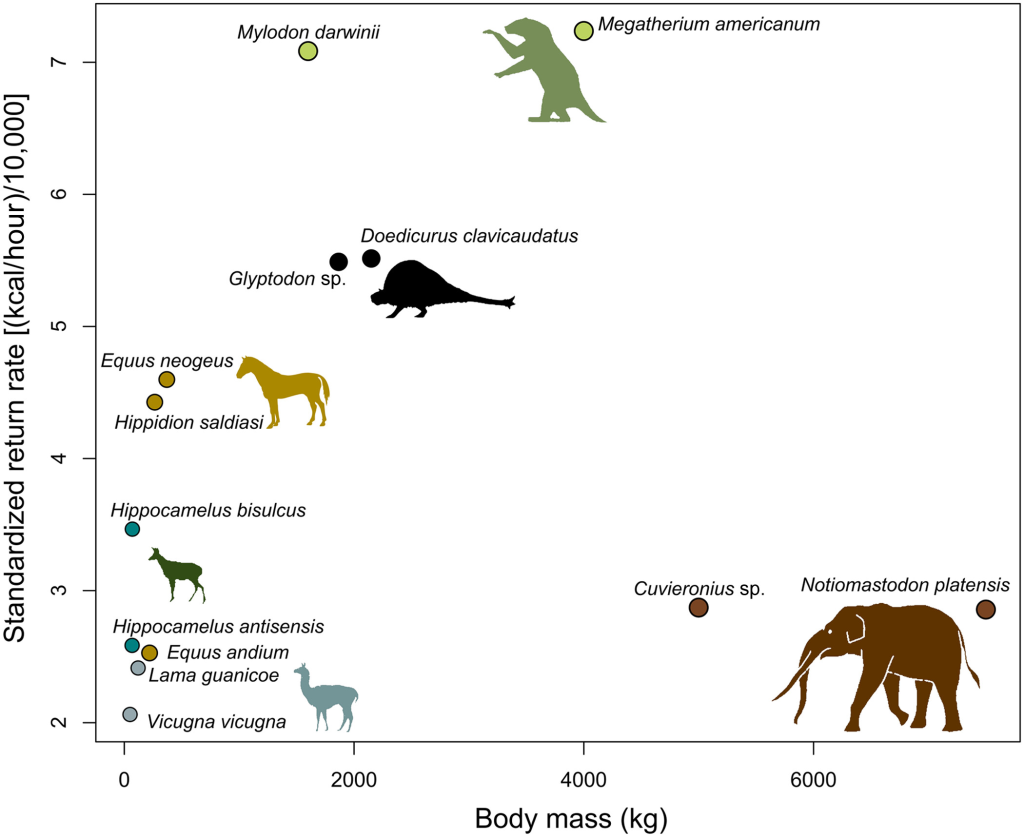

Across 20 carefully dated archaeological sites in Patagonia, the Pampas, and central Chile, giant prey dominated the bone piles. In some places, more than 90% of the remains belonged to extinct megafauna like giant sloths, horses, and gomphotheres (relatives of elephants).

Evidence of butchering—cut marks, percussion fractures, and burned bones—proved humans weren’t just scavenging. They were hunting these giants, and doing so regularly.

The findings even line up with economic models of hunting behavior. Using a “prey choice model,” scientists rank species by the calories they provide versus the effort needed to capture them. Giant sloths topped the charts. Guanacos, deer, and smaller animals—long thought to be staples—actually ranked much lower. Yet after the giants vanished, these smaller prey suddenly took center stage.

It’s the same story we see in fishing villages today: when the big, profitable fish are gone, people shift to smaller, less rewarding catches.

A Local Lens: Patagonia to Nigeria

Think of a Patagonian hunter 12,500 years ago. One giant sloth could feed a whole community, provide hides for shelter, and bones for tools. Why chase dozens of guanacos when one massive carcass delivered it all?

The logic isn’t unique. In Nigeria today, bushmeat hunters often target large antelope, even though smaller animals are easier to catch. In India’s fishing villages, bigger catches are always prized. Across cultures, people naturally aim for “more bang for the buck.” The ancient South American foragers were no different.

The Cascade Effect

Here’s the twist: the giants weren’t just food. They were ecosystem anchors. Remove them, and the web of life destabilizes. A moderate level of human hunting—especially targeting keystone species—was enough to tip fragile Pleistocene ecosystems into collapse.

Once megafauna numbers dropped, extinction cascades followed. By 11,600 years ago, they were nearly all gone. Humans, in turn, were forced to broaden their diets, shifting to guanacos, deer, and small mammals. The great feast was over.

Why This Matters Now

This isn’t just a story about the past. It’s a warning about the present. Humans today still overexploit the “biggest and best”—tuna, elephants, old-growth forests. The South American record shows how quickly abundance can collapse when societies depend too heavily on a few high-reward species.

And in a warming world, where ecosystems are already strained, our actions matter even more. The late Pleistocene extinctions remind us that climate stress plus human pressure is a deadly mix.

Keeping Curiosity Alive

So the next time you see a museum skeleton of a giant ground sloth, don’t just marvel at its size. Ask yourself: what choices did humans make that sealed its fate? And what choices are we making now with our oceans, forests, and wildlife?

Because here’s where it gets interesting: the same strategies that led to loss thousands of years ago—favoring short-term gain over long-term balance—are still with us. The question is whether we’ll recognize the pattern in time.

Let’s Explore Together

This new study doesn’t just rewrite history. It challenges us to think forward.

- Could lessons from the Pleistocene guide how we manage today’s fisheries, forests, or farmlands?

- If you were part of that ancient research team, what would you test next—dietary DNA, hunting tools, or climate records?

- And closer to home: what everyday resource in your community is at risk of being “hunted out” too fast?

The giants of South America are gone. But the science of their story is alive, urging us to look at our own footprints with clearer eyes.