This Study Could Make Atomic Imaging Affordable

One of my favorite “types” of videos has always been powers of ten. Through telescopes, we can see many of the large-scale structures in the universe. Seeing the little guys, though, that’s been challenging.

To see atoms clearly, scientists have long relied on huge, expensive transmission electron microscopes (TEMs) that demand high voltages, specialized rooms, and expert operators. These machines, capable of resolving details smaller than a tenth of a nanometer, have been the crown jewels of research institutions. But what if that level of precision could come from a smaller, cheaper, and more accessible microscope?

That’s exactly what a new study published in Nature Communications has just demonstrated. A team led by Arthur Blackburn at the University of Victoria has achieved sub-ångström (0.67 Å) resolution using a 20 keV scanning electron microscope (SEM)—a device normally found in many modest labs around the worlds41467-025-64133-3.

In plain language: they’ve made a regular electron microscope see individual atoms, without the usual multi-million-dollar upgrades.

Rethinking How We See the Smallest Things

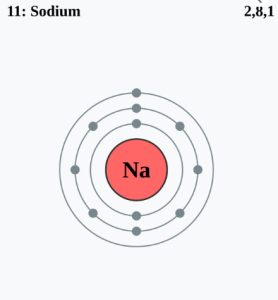

In materials science and biology, seeing is everything. Researchers want to visualize not just shapes, but atomic arrangements—how layers of carbon fold into graphene, how a defect spreads in a crystal, or how a protein bends and bonds. Traditionally, that kind of detail required TEMs running above 30 keV, fitted with aberration correctors and ultra-sensitive detectors. These instruments, though powerful, come with staggering costs and complexity.

The team’s innovation flips this model. Instead of throwing more power at the problem, they turned to ptychography—a computational imaging technique that reconstructs high-resolution images from overlapping diffraction patterns. The approach uses mathematics to fill in what the microscope can’t directly capture.

Think of it like turning a blurry set of puzzle pieces into a crystal-clear image by studying how light—or in this case, electrons—scattered when it hits them.

The Breakthrough: Sub-Ångström Vision at Low Energy

Using a 20 keV SEM in transmission mode, Blackburn’s team achieved a resolution of 0.67 angströms—less than a tenth of a nanometer, or about the width of a single hydrogen atom. That’s roughly eight times sharper than what a standard SEM can normally deliver.

The key was combining three technologies:

- A cold field emission source, which produces a highly coherent electron beam.

- A hybrid direct detector optimized for low-energy electrons.

- A multi-slice ptychographic reconstruction algorithm, capable of correcting distortions in the diffraction data digitally instead of relying on expensive optical correctors.

This algorithm effectively “undoes” the lens imperfections that limit normal microscopes, producing an image of gold nanoparticles and molybdenum disulfide (MoS₂) at a clarity once thought impossible at such low energy.

The result isn’t just an incremental improvement—it’s a paradigm shift.

Why Lower Energy Matters

Lower beam energy might sound like a downgrade, but it’s actually a blessing for many applications. High-energy electrons can damage fragile samples like biological molecules or 2D materials. Lower energies reduce that damage, allowing scientists to capture fine details before a sample disintegrates.

Blackburn’s setup also takes advantage of a physics sweet spot. At lower energies, electrons scatter more strongly off atoms, producing higher contrast images of thin samples. That’s particularly valuable for materials made of lighter elements—like carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen—that make up everything from biological tissues to flexible electronics.

This could make high-resolution imaging of thin, light materials—such as graphene, MoS₂, or even small proteins—possible in labs without access to cryo-electron microscopes.

For researchers in India, Nigeria, or Brazil, where infrastructure costs can be prohibitive, the implications are enormous. Imagine a materials science department at a regional university being able to image individual atoms in a solar cell layer or track defects in a semiconductor using an upgraded SEM instead of a multimillion-dollar TEM suite.

A Story of Elegant Engineering

One of the most striking elements of the paper is how the team solved a problem that every microscopist faces: distortion. Electron beams passing through magnetic lenses tend to bend in subtle ways, introducing “pincushion” distortions that make images less reliable. Blackburn’s group didn’t rebuild the hardware—they corrected it mathematically.

By comparing the expected and observed diffraction patterns from gold nanoparticles, they developed a distortion model that could digitally “unwarp” the data. The reconstructed image aligned with reality to within 0.5% accuracy, an extraordinary level of precision achieved entirely in software.

It’s a perfect example of what modern science often looks like: hardware and algorithms working hand-in-hand, each amplifying the other’s strengths.

The Bigger Picture: Democratizing Atomic-Scale Imaging

The most exciting part of this breakthrough isn’t just the numbers—it’s the accessibility.

Traditional high-resolution TEM systems cost millions of dollars and require specialized infrastructure. By contrast, SEMs are far more common. Blackburn’s method suggests that with smart algorithms and careful calibration, even modest microscopes could achieve atomic resolution.

This could accelerate discoveries in multiple fields:

- Nanotechnology: Visualizing the arrangement of atoms in 2D materials or nanoparticles used in sensors and catalysts.

- Biology: Imaging small proteins (<100 kDa) that have remained invisible to conventional cryo-EM.

- Education: Training a new generation of microscopists without the steep barrier of elite facilities.

It’s also a powerful reminder that innovation doesn’t always mean building bigger machines—it can mean thinking smarter about the tools we already have.

Where It Goes Next

Blackburn’s team notes that their technique is not yet ready to image living cells or large biomolecules at atomic resolution. Those require further algorithmic advances and perhaps hybrid approaches that blend ptychography with single-particle analysis—a cornerstone of modern cryo-EM.

Still, achieving sub-ångström resolution at one-quarter the beam energy of conventional microscopes marks a major milestone. It points toward a future where atomic-scale imaging could become a standard capability, not a luxury.

As computing power grows and open-source imaging algorithms proliferate, even small labs could join the frontier of atomic visualization.

Let’s Explore Together

If a humble 20 keV electron microscope can now “see” individual atoms, what else might we make accessible through smarter science?

- Could your local lab retrofit its SEM to explore 2D materials or protein crystals?

- How might this change collaborations between resource-rich and resource-limited institutions?

- And what other hidden capabilities might we unlock by combining old tools with new algorithms?

Science just showed us that sometimes, the most profound progress comes not from new machines—but from new ways of seeing.