Hidden Ecosystems of the Ordovician

Every fossil story begins with loss. Sediment buries life, time hardens it, and chance decides what survives. For the Ordovician Period—roughly 485 to 444 million years ago—that loss has long been severe. While the Cambrian Explosion left us famous sites like the Burgess Shale, its Ordovician successors seemed strangely quiet. Paleontologists saw only fragments of shell and bone, not the bustling soft-bodied life that surely filled those seas.

But a recent PNAS paper by Giovanni Mussini and Nicholas Butterfield changes that narrative. Hidden deep beneath the plains of North Dakota, in two oil-exploration drill cores, the team found exquisitely preserved microfossils—tiny carbon films of worms, mollusks, crustaceans, and even early eurypterids (sea scorpions). These “small carbonaceous fossils,” or SCFs, open a microscopic window into what ordinary life looked like in well-oxygenated, shallow seas—ecosystems that until now were all but invisible.

A Window Beneath the Prairie

The story starts in Renville County, North Dakota, where drill bits passed through two rock layers: the Cambrian–Ordovician Deadwood Formation and the younger Winnipeg Formation. Each belongs to a different marine transgression, times when seas flooded the North American continent. In both layers, Mussini and Butterfield found thousands of microscopic fossils so fine they preserved individual teeth, scales, and bristles smaller than a grain of pollen. They call the older set the lower Osterberg biota and the younger one the upper Osterberg biota.

Why does that matter? Because these fossils come from normal, sunlit shelf waters—not the oxygen-poor, restricted basins that usually yield “exceptional preservation.” For the first time, scientists can glimpse the everyday Ordovician ocean rather than its rare backwaters.

The Creatures That Time Forgot

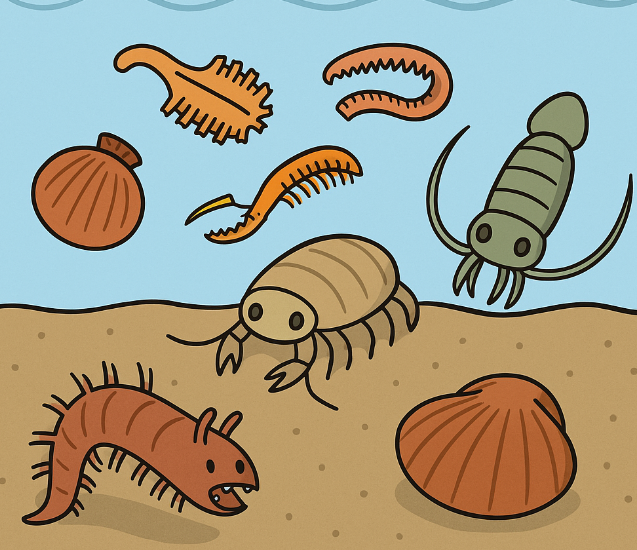

Under a scanning-electron microscope, each flake of shale turned into a miniature zoo.

- Mollusks showed chitinous feeding ribbons—radulae—with rows of recurved teeth. Some resembled modern grazers, while others appeared built for predation, suggesting that snail-like hunters already roamed the sea floor 470 million years ago.

- Annelids (left their jaws and bristle bundles): these were early cousins of today’s polychaete worms, equipped with serrated mouthparts for slicing prey.

- Priapulid worms displayed tiny comb-shaped teeth ideal for scooping micro-particles—evidence of sediment “vacuuming” that kept Ordovician sea floors clean.

- Crustacean-like arthropods revealed grinding molars patterned with micrometer-scale ridges, the oldest known proof of chewing machinery adapted for crushing plankton or detritus.

- And perhaps most striking, fragments of eurypterid-type cuticle—complete with pores for sensory hairs and gas-exchange organs—pushed the origin of these iconic “sea scorpions” tens of millions of years earlier than thought.

Each specimen was less than a millimeter long, yet together they redrew an entire ecosystem.

Rewriting Evolution’s Timeline

Until this discovery, scientists assumed that most Cambrian-style soft-bodied communities vanished early in the Ordovician, replaced by shell-bearing animals that dominate the fossil record. The Osterberg biotas tell a subtler story: those “modern” shells evolved alongside a hidden cast of soft-bodied grazers, scavengers, and predators. In fact, the new fossils look more modern than their famous Cambrian relatives—proof that evolutionary innovation on the continental shelves continued long after the Cambrian Explosion.

The findings also suggest that the celebrated Burgess Shale and Fezouata biota, both of which formed in deeper or oxygen-poor settings, may be ecological outliers. The real engine of Ordovician life—the open, oxygen-rich seas—was alive with creatures we simply hadn’t been able to see until now mussini-butterfield-2025-two-ex….

From North Dakota to the World’s Coastlines

For geologists drilling through prairie rock, it’s astonishing to realize that those sediments once lay beneath warm equatorial waters. Imagine coastal Pakistan or West Africa today—broad, sunlit shelves teeming with crustaceans and algae. That was North Dakota 470 million years ago. The study reminds us that even seemingly ordinary marine muds can hide extraordinary records if we look closely enough.

And for countries rich in oil or mineral exploration data—from Nigeria’s Benue Trough to Brazil’s Paraná Basin—the message is powerful: old drill cores may hold the next revolution in paleontology. High-resolution imaging and careful acid digestion techniques can transform industrial samples into time capsules of ancient life.

A Twist in the Fossil Record

Mussini and Butterfield’s work prompts a reevaluation of why exceptional preservation declined after the Cambrian. Perhaps the decline wasn’t purely chemical or environmental; maybe we just hadn’t been looking small enough. Microscopic fossils can survive conditions that destroy larger carcasses. Their study suggests that much of early animal history remains locked at the microscale, waiting to be revealed in cores and sediments worldwide.

“But here’s where it gets interesting,” Butterfield notes in the paper, the Ordovician ocean may have been full of “cryptic, modern-style faunas” we’d mistaken for empty. In other words, the story of life’s great radiation was never interrupted—just hidden.

Let’s Explore Together

The Osterberg biotas are more than ancient curiosities; they’re reminders that science often advances by peering into overlooked corners—whether in a forgotten drill core or a drop of acid that frees a 470-million-year-old worm tooth.

So let’s keep the conversation going:

- Could your region’s geological surveys hide similar microfossil treasures?

- What technologies might reveal invisible life in other time periods—or even on Mars?

- And what everyday data—cores, archives, images—might rewrite the stories we thought we knew?