What Is a Gravastar? The Strange Star That Might Replace Black Holes

A recent idea in astrophysics suggests that some objects we call black holes might actually be something very different — and much stranger.

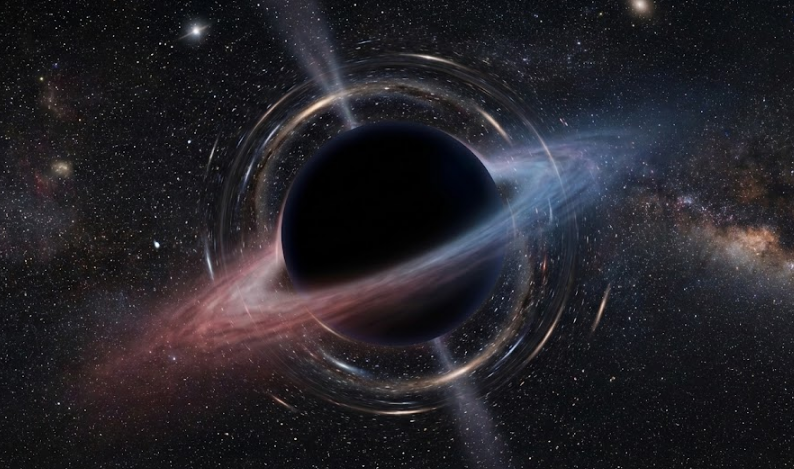

For decades, black holes have been the “end of the road” in astronomy. When a massive star collapses, its gravity becomes so strong that nothing, not even light, can escape. That creates an event horizon — a boundary you can cross but never return from.

But what if this picture is wrong?

Some physicists have proposed an alternative: the gravastar, short for gravitational vacuum star. Gravastars behave like black holes from afar, but inside, they are completely different. And if real, they could solve some of the biggest puzzles in physics.

Let’s break down what a gravastar is.

A gravastar looks like a black hole from the outside… but there’s no event horizon.

The idea was first introduced by Mazur and Mottola in the early 2000s. Later studies expanded the theory and tested whether gravastars could exist in stable form.

Here’s the basic structure:

1. A “bubble” of repulsive energy at the center

Inside a gravastar is a strange state of matter similar to dark energy, where pressure is negative (p = –ρ). This creates a repulsive effect — the opposite of gravity — and prevents a singularity from forming.

2. A thin shell of ultra-stiff matter

Surrounding that core is a thin shell made of extremely dense, “stiff” material where pressure equals energy density (p = ρ). This shell acts like a protective wall.

3. A normal exterior

Outside the shell, spacetime looks just like the space around a black hole, following the standard Schwarzschild solution from general relativity.

From far away, a gravastar and a black hole behave almost identically. Light bends the same way. Objects orbit the same way. That’s why gravastars were proposed as a viable alternative to black holes.

Why Propose a Gravastar at All?

Gravastars were created to fix two major problems with black holes:

Problem 1: The singularity

Black holes require matter to collapse into a point of infinite density. Physics breaks down there. Gravastars avoid this entirely because their interior is filled with dark-energy-like pressure rather than crushed matter.

Problem 2: The information paradox

According to quantum physics, information shouldn’t be destroyed — but black holes seem to erase it. In a gravastar, the event horizon never forms, so information never becomes trapped. Some researchers argue this resolves the paradox.

How Gravastars Differ From Black Holes

Gravastars and black holes may look almost identical from far away, but their interiors could not be more different. A black hole has an event horizon and a central singularity, where matter collapses into infinite density. A gravastar has no event horizon and no singularity. Instead, its center is filled with a dark-energy-like vacuum, surrounded by a thin shell of ultra-stiff matter.

Even with these major internal differences, both objects appear nearly the same externally because they can be extremely compact—almost the exact size of their Schwarzschild radius. In fact, gravastars can be built with compactness arbitrarily close to that of a black hole. This makes them very difficult to distinguish using ordinary telescopes.

Can We Tell a Gravastar From a Black Hole?

Although telescopes struggle to tell them apart, gravitational waves may offer a clear way to identify gravastars. When two ultra-compact objects merge, they vibrate like a ringing bell. These vibrations—called quasi-normal modes—show up in data from detectors such as LIGO. Studies show that gravastars are stable against many types of disturbances, but their vibrations fade (or “damp out”) at different rates than those of black holes. In other words, a gravastar’s ringdown has a different signature than a black hole’s. This makes gravitational-wave astronomy one of the most promising tools for spotting a real gravastar.

Are Gravastars Real or Just Theory?

Right now, gravastars are still theoretical. Scientists have created detailed mathematical models, tested their stability, and explored many versions, including gravastars with charge, rotation, anisotropic pressures, extra dimensions, and even primordial gravastars that might have formed in the early universe.

But so far, no observation has confirmed or ruled out their existence. Current instruments can’t easily distinguish gravastars from black holes, though future gravitational-wave detectors may finally settle the question.

Why Gravastars Matter for Modern Physics

Even if gravastars never turn out to be real objects, the idea itself is incredibly useful. Gravastar research helps scientists explore big questions: What actually happens when a star collapses? Are singularities physically possible? How do gravity and quantum physics fit together? Could other exotic compact objects exist? By challenging the traditional black hole model, gravastars help researchers test the limits of Einstein’s theory and imagine new possibilities for the structure of spacetime.

The Bottom Line

A gravastar is a bold alternative to a black hole. Instead of a singularity, it contains a bubble of repulsive energy wrapped in a thin, ultra-dense shell. From the outside, it looks nearly identical to a black hole—but inside, the physics could be completely different. Whether they exist or not, gravastars push scientists to rethink how the universe works and what might lie inside the most mysterious objects in space.