The Brain’s Great Bridge

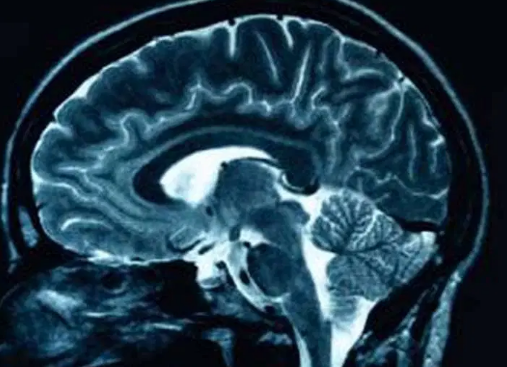

Every thought you have—reading this, feeling curious, moving your eyes across the screen—depends on a thin arch of tissue buried deep inside your brain. It’s called the corpus callosum, and it’s the largest bridge of nerve fibers connecting your brain’s two halves. For decades, scientists have known that when this bridge falters, thinking, feeling, and coordination can stumble. However, until now, no one has really understood how our genes influence it.

A new study, conducted by researchers at the University of Southern California, VU Amsterdam, and the QIMR Berghofer Institute in Australia, utilized artificial intelligence and genetic data from over 46,000 individuals to map the genetic blueprint of the human corpus callosum (CC). Their results reveal that the bridge between your hemispheres is not just one structure—it’s a collection of genetic stories unfolding from before birth, shaping everything from how you think to how your brain ages.

A Digital Autopsy of the Brain

To understand the CC’s genetics, the team built an AI tool called SMACC (Segment, Measure, and AutoQC the mid-sagittal Corpus Callosum). Think of it as a digital archaeologist for brain scans: it uses MRI images to precisely outline the CC, measure its thickness and shape, and even detect subtle regional differences.

Using SMACC, they analyzed brain scans from two large public datasets—the UK Biobank, which includes middle-aged and older adults, and the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study, which tracks the development of children and teens. Together, these provided a rare chance to see how genes influencing the CC may act across a lifetime—from a 10-year-old’s developing brain to an adult’s slowly thinning one.

Genes That Build (and Sculpt) the Brain’s Bridge

The researchers identified 48 genetic regions linked to the CC’s total size and 18 more tied to its thickness. Some genes were especially revealing:

- IQCJ-SHIP1: helps organize nerve fiber connections, influencing how efficiently signals jump across neurons.

- HBEGF: a growth factor guiding early brain cell migration.

- STRN: involved in Wnt signaling, a key pathway for brain development.

Interestingly, genes associated with cell death and immune system regulation—such as FOXO3—appear to regulate how certain regions of the CC thicken over time. That suggests parts of our brain’s wiring are “pruned” through a genetic program of cleanup and refinement, similar to how gardeners trim branches for healthy growth.

This pruning is strongest in the posterior CC—the area connecting sensory and parietal brain regions. These zones mature later and are more responsive to experience, hinting that your environment and genes may work together to sculpt how your two brain halves communicate.

The Brain’s Blueprint Has a Direction

Surprisingly, the genetic influence on the CC follows a gradient from front to back. Different sets of genes shape the front (genu), middle (body), and back (splenium) regions—each tied to distinct brain functions like planning, movement, and vision.

This pattern mirrors how the brain develops: front areas (linked to reasoning and control) mature last, while sensory regions at the back are fine-tuned early. That suggests the CC grows and reshapes itself in sync with how the brain’s “neighborhoods” evolve—a genetic choreography stretching across decades.

A Bridge with Many Connections

The study also revealed genetic overlap between the CC and the cerebral cortex, the outer layer of the brain. Some genetic variants that make the CC larger were linked to a thinner cingulate cortex—a region involved in emotion and attention. Others tied the CC’s rear section to thicker visual regions.

In short, the same genes can strengthen one brain area while refining another—like a contractor adjusting both the bridge and the roads it connects.

Ties to Mental Health and Movement

Genes shaping the corpus callosum also overlap with those affecting ADHD, bipolar disorder, and even Parkinson’s disease..

- People with a genetically smaller front CC (genu) tend to have higher ADHD risk, echoing studies showing weaker cross-hemisphere attention networks.

- Thinner rear regions (splenium) were genetically linked to bipolar disorder—potentially explaining mood-regulation disruptions.

- Some of the same genetic signatures influencing CC thickness also affect MAPT, a gene tied to Parkinson’s and abnormal protein buildup in brain cells.

Together, these findings suggest that subtle variations in how the hemispheres communicate may ripple outward, shaping not only cognition but also vulnerability to disease.

A Universal Blueprint of Connection

Across ancestry groups, the findings held remarkably steady: 82% of genetic effects seen in Europeans appeared in non-European participants too. That’s a critical step toward global neuroscience that reflects more of humanity.

And because the CC’s structure forms early in life—many genes acting before birth—this research hints at new opportunities for early detection and intervention in developmental and psychiatric disorders.

Why It Matters Beyond the Lab

For a child struggling with attention, a teen showing mood swings, or an older adult facing memory loss, understanding the brain’s “main bridge” could open new diagnostic and therapeutic paths. Instead of just scanning for brain size, future clinicians might look at the genetic fingerprints of white matter—searching for early signs of how neural communication is wired or miswired.

In low-resource settings where MRI scanners are scarce, genetic screening or AI-powered imaging tools like SMACC could help identify neurodevelopmental risks earlier, guiding interventions long before symptoms appear.

The Science of Connection

If the brain were a city, the corpus callosum would be its main highway—carrying messages from one side to another at lightning speed. This new research shows that our mental “infrastructure” isn’t built randomly. It’s designed by a genetic blueprint that balances growth, pruning, and communication in a lifelong dialogue between biology and experience.

But here’s where it gets interesting: those same highways can reveal where traffic jams—or miswirings—occur in disorders from ADHD to Parkinson’s. The next challenge? Using this map to understand how to repair or reroute the flow.

Let’s Explore Together

- Could understanding your brain’s genetic “bridge” explain why some people are more creative, emotional, or focused than others?

- If we could strengthen cross-hemisphere communication through training or stimulation, would it change how we think?

- What would you test next if you were part of this research team?