When Weather Hits Predator–Prey Systems

A single cold snap can silence an entire hillside of insects in a matter of hours. But here’s the twist: the real danger isn’t the sudden drop in temperature—it’s what that shock does to the delicate choreography between predators and the invasive prey they’re meant to control. A new study in Scientific Reports digs deep into this problem using advanced reaction–diffusion models, uncovering when ecosystems bounce back—and when they fail in ways we didn’t expect

This matters everywhere—from farmers in Brazil struggling with crop-eating pests, to forest managers in the U.S. trying to keep invasive beetles from swallowing entire regions of woodland. Biological control only works when the predator keeps up. Extreme weather might break that balance.

Tiny Errors, Big Consequences: Why Weather Shocks Matter

Think about cooking rice over a charcoal fire. If a sudden gust of wind kicks up, your pot might sputter but ultimately recover. But if the wind keeps shifting the flame—or if it hits just as the water hits boiling—the whole batch can fail. Predator–prey systems behave the same way.

The researchers introduce weather shocks into the predator–prey equations in two ways:

- Short-lived disruptions—like a heatwave that knocks population sizes down briefly.

- Long-lasting rate changes—like drought raising mortality or altering reproduction conditions over entire seasons.

Here’s what surprised the team: brief population dips alone almost never change the final outcome. The system’s “traveling waves”—spreading fronts of prey or predators—are remarkably stable against temporary chaos. Even strong random disturbances, including harsh Lévy-type shocks that mimic rare extreme events, faded as the system returned to the same long-term trajectory.

But persistent parameter changes? Entirely different story.

A slight shift in predator mortality or prey reproduction could cause the system to transition from successful control to runaway invasion.

In other words: ecosystems are numerically resilient… until they’re not.

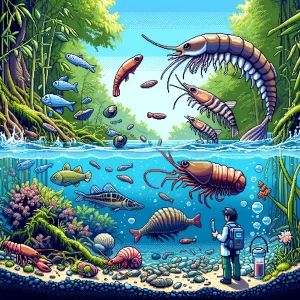

The Traveling Wave: Nature’s Hidden Conveyor Belt

Across a farm field in India or a wetland in Nigeria, species don’t spread randomly—they move as “traveling waves.” Think of these like the edge of a slowly advancing tide: behind the front, prey or predators thrive; ahead of it, they have yet to arrive.

When the authors solved the model analytically—a rare achievement—they could map out exactly how quickly the wave should move, which equilibrium it should approach, and whether predators could suppress the prey long-term.

Their key insight: Extreme weather doesn’t just knock populations around. It can change the actual wave the system selects—determining who ultimately wins.

Here’s the tension:

- If the prey front moves forward faster than the predator can catch up, invasion succeeds.

- If predators stay proportionally strong (above a threshold), both species can collapse together—a biocontrol success.

- If weather raises the prey’s “Allee threshold” (the minimum population needed to grow), even a stable predator may fail to keep up.

This contrast—between resilient short-term numbers and fragile long-term dynamics—is one of the study’s most important takeaways.

Lessons From the Math: Who Survives and Who Doesn’t?

Across dozens of simulations, the model revealed three real-world patterns:

1. Prey Wins When Weather Raises Predator Mortality

In drought-stressed regions—such as northeastern Brazil—predator species may decline more rapidly during hot spells. When predator mortality (σE) increases, the prey wave continues to march forward, leaving the predators behind. The study illustrates this exact scenario: predators vanish, prey dominate, and control fails.

2. Both Species Collapse When Predators Stay Proportionally Strong

This is counterintuitive but powerful. When predator density stays above u / √d, both predator and prey can crash to zero.

For managers fighting invasive pests—emerald ash borer in North America, like the dead trees in my backyard, armyworms in Africa—this is the ideal outcome. The mathematics predicts the precise parameter window where this happens.

3. Mixed Outcomes Are Possible Under “Bistable” Conditions

In parts of the world where weather is highly variable, the system can flip between:

- coexistence,

- full invasion,

- joint extinction.

The model even predicts wave fronts that connect coexistence in one region to extinction in another—like wildfires that burn unevenly across different landscapes. These bistable conditions are especially sensitive to weather-induced parameter shifts, meaning policy decisions or ecological interventions have disproportionate leverage.

A Global Perspective: Why Readers Everywhere Should Care

Whether you’re working in a lab in Lagos or running a field site in rural China, the takeaway is universal:

Climate variability changes ecological outcomes not by chaos, but by nudging key biological rates across invisible thresholds.

Farmers, ecologists, and conservation planners often assume extreme weather “knocks things back but they recover.” The study shows this is only half true.

- Temporary disturbances? Usually fine.

- Parameter changes in prey reproduction, predator mortality, or crowding? Potentially ecosystem-shifting.

This matters for biological control everywhere—from parasitoid wasps in U.S. forests to ladybird beetles in Southeast Asian farms.

Let’s Explore Together

This study opens the door to deeper conversations about climate, ecology, and long-term stability. Here are a few questions to spark reflection:

- Could this idea work in your region’s biocontrol program?

- If you were on the research team, which environmental factor would you test next—heatwaves, drought, flooding, or disease?

- What everyday ecological problem in your community do you wish science could model this way?

I’d love to hear how this research connects to your work, your community, or your field site.