Can Stars Die Twice?

Every star you see in the night sky will one day fall silent. But according to new research, the silence won’t last forever. Billions of years after their final breath, some stars may explode again—triggering the last fireworks in the universe.

That surprising idea comes from astrophysicist Matthew Caplan, who explored a cosmic puzzle most scientists rarely touch: What happens to white dwarfs—those dense, Earth-sized stellar remnants—after the universe grows cold, dark, and still?

And the answer is stranger, slower, and more awe-inspiring than anyone imagined.

The Universe’s Most Patient Bombs

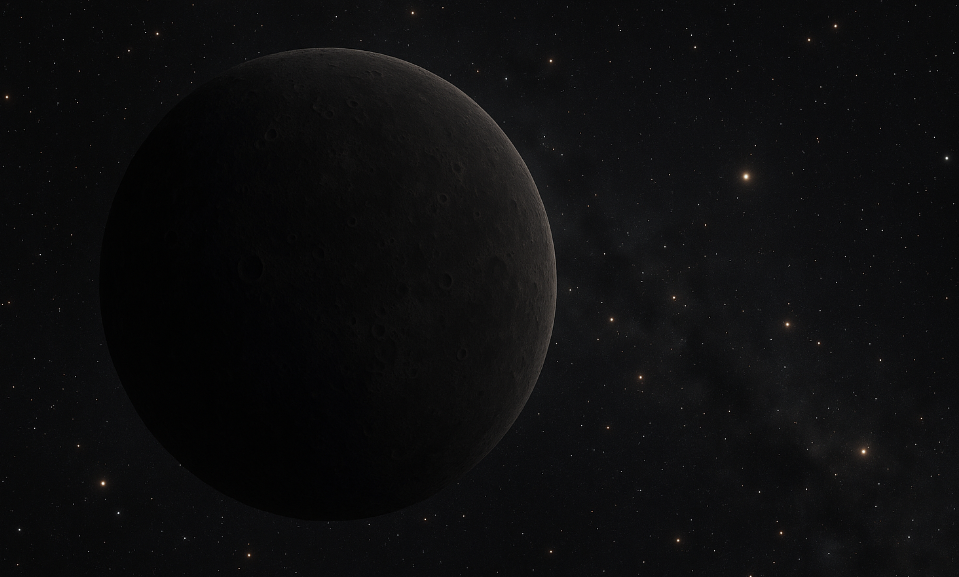

No matter where you live, you probably know the rhythm of heat and light—sunrise, streetlights, power grids humming through the night. Now picture a time when the universe has no light at all. No stars. No galaxies in the form we know. Just ancient, cold remnants drifting apart.

These remnants are white dwarfs, the final stage for most stars, including our Sun. Over unimaginable spans of time—longer than the age of Earth, the Sun, and even the universe—they cool until they are essentially frozen spheres of carbon, oxygen, and heavier elements. Astronomers call these future corpses black dwarfs.

But Caplan’s research shows that these dark relics don’t simply sit quietly forever. Instead, they slowly change inside, in a way that no one standing in the 21st century would ever witness—but that physics demands.

And here’s where the twist starts.

A Star That Turns Into Iron in the Dark

Inside a black dwarf, the nuclei are packed tightly, arranged like spheres in a crystal. Even though the star is cold—near absolute zero—its atoms still move. Quantum mechanics ensures that particles can tunnel through energy barriers, even when classical physics says they shouldn’t.

So something remarkable happens: Black dwarfs slowly fuse their elements into heavier ones, step by step, even without heat.

Silicon fuses into nickel. Nickel decays into iron-56, one of the most stable nuclei in the universe. Bit by bit, atom by atom, the core of a black dwarf turns into iron.

This process is called pycnonuclear fusion, and it is so slow that the predicted timescale borders on the unbelievable: 10¹¹⁰⁰ years for the heaviest black dwarfs. That’s a 1 followed by 1,100 zeros—a number so large it makes geological and cosmological time look tiny.

But this microscopic change leads to a macroscopic catastrophe.

The One Number That Triggers Collapse

A white dwarf survives because electrons resist being squeezed—a quantum pressure that holds up the star against gravity. But this only works if the star has enough electrons. Iron-56, however, has fewer electrons per nucleon than lighter elements. As the core gradually turns into iron:

The electron fraction drops.

The support weakens.

The maximum mass the star can support—the Chandrasekhar limit—falls.

Eventually, the star finds itself too massive for its now-weakened structure. And then, after trillions upon trillions of years of stillness, it collapses.

The collapse could create something very much like a supernova: a burst of neutrinos, shockwaves racing outward, and possibly even a neutron star at the center. These would be the last supernovae the universe will ever produce.

A Global View: Why Scientists Everywhere Should Care

If you work in a lab in Brazil, teach physics in Kenya, or study stars from a rooftop in Hanoi, this research highlights a broader truth about science: Nature doesn’t stop surprising us, even in the extremes.

And this particular extreme—dead stars exploding after 10¹¹⁰⁰ years—connects with ideas central to physics everywhere:

- Quantum tunneling: Used in nuclear reactors, semiconductors, and even medical imaging.

- Degenerate matter: Relevant in high-pressure materials research and planetary core modelling.

- Cosmic evolution: Critical for understanding where our own Sun will eventually end up.

It also reminds us that science can explore impossibly distant futures not through guesswork, but by following the logic of known physics.

The Human Story Hidden in the Numbers

Think of a black dwarf like a slow-cooking clay pot in a traditional kitchen in rural India or Ghana. Even after the fire goes out, the pot stays warm, and things inside continue to transform long after anyone expects. A black dwarf is similar—except the “kitchen” is the entire universe, and the “cooking time” is longer than any human language has a word for.

And the result? A flash of light in a universe that has forgotten what light is.

What This Means for the Universe’s Final Act

Caplan calculates that around 1% of all stars in the observable universe—about 10²¹ of them—will eventually explode this way, provided protons remain stable. staa2262

But because the universe is expanding faster and faster, each explosion will happen in utter isolation. By the time the first black dwarf collapses, every other star and remnant will be so far away that light from one explosion will never reach another. Each will be a lonely firework in a sky that no longer has observers.

Let’s Explore Together

This study pushes imagination to its limits, but it also deepens our understanding of what stars—and physics—are capable of.

Here are a few questions to spark discussion:

- Could this kind of slow fusion happen in other extreme environments?

- If you were designing a simulation for this process, what would you test first?

- What everyday system—from batteries to buildings—changes slowly over time the way black dwarfs do?

Curiosity doesn’t need a timescale. Whether 10⁶ years or 10¹¹⁰⁰ years, the universe always has another story to tell.