Killer Whales Are Hunting Juvenile Sharks

Two years. Same place. Same outcome. Juvenile great white sharks, about the size of a classroom table, were attacked and killed by killer whales in the Gulf of California. Until recently, scientists believed these interactions were almost unheard of. But new evidence suggests something is changing beneath the surface.

And if you work in shark ecology, marine conservation, or climate-linked species shifts, this finding raises urgent questions

A Predator We Rarely See at Work

Killer whales and white sharks share the top of the marine food web, but they almost never interact directly. Most previous cases involved large adult sharks, hunted for their livers—one of the most energy-rich organs in the animal kingdom.

But this new study documents repeated predation on much smaller juveniles—around 2 meters long—in Mexican waters. That’s a big deal for three reasons:

- Juvenile sharks aren’t usually targeted.

- These events happened two years apart, in nearly the same location.

- Killer whales used highly coordinated and specialized hunting techniques.

So what changed?

Why This Matters for Young Sharks

In most parts of the world, juvenile white sharks grow up far from adults, spending their early years in warmer nursery zones. These areas are thought to be relatively safe from large predators.

But warming oceans are rewriting that rule.

Scientists have already observed poleward shifts and redistribution of young white sharks linked to marine heatwaves and events like El Niño.

And when animals move—so do their risks. In the Gulf of California, killer whales are present year-round and have already been documented hunting several shark species, from bull sharks to whale sharks.

Now, juvenile white sharks appear to be added to the menu.

What the Videos Revealed

The research team captured two rare events—one in August 2020, another in August 2022—using drones and underwater cameras. The footage shows:

- killer whales striking from below,

- flipping the shark upside down,

- inducing tonic immobility—a temporary paralysis in sharks,

- and removing only the liver before discarding the body.

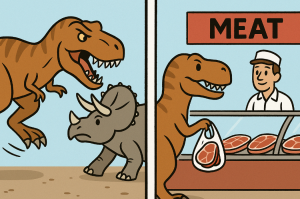

The liver was then shared among pod members, including calves. This suggests learned behavior rather than opportunistic feeding.

The researchers identified individuals previously seen preying on rays and other sharks—indicating a specialized hunting pod, now informally known as the “Moctezuma pod.”

A Small Vulnerable Population Meets a New Threat

White sharks in this region already face:

- accidental capture in fisheries,

- slow reproduction (females give birth only every few years),

- and habitat shifts linked to warming waters.

Adult white sharks can detect killer whales and evacuate feeding sites for months—something documented in South Africa and California.

Juveniles, however? They may not yet know what to fear. And unlike adults, they can’t simply leave nursery areas without risking starvation.

So what happens if predation becomes seasonal and repeated? The authors raise three possibilities:

- Juvenile mortality could increase.

- Nursery sites could lose their function.

- A new predator-prey dynamic may be emerging.

But there’s one more twist.

Is This a Local Event—or a Global Pattern?

Before this study, only one confirmed case of orcas hunting a juvenile white shark existed—off South Africa Now, a second location shows:

- repeated events,

- similar timing,

- similar prey size.

If climate change continues shifting species distributions, interactions once considered “rare” may become routine. That means researchers now face new questions:

- Are killer whales expanding their hunting strategies?

- Are young sharks moving into riskier waters?

- Or are both species simply colliding as oceans warm?

But this part is clear—the oceans are changing faster than we can observe.

What Happens Next?

The authors outline three priorities for future research.

- Track shifting nursery ranges as temperatures rise.

- Test whether juvenile sharks develop avoidance behavior similar to adults.

- Determine whether attacks are increasing, or if these are still rare events.

For marine scientists with limited resources—especially those outside large research hubs—this study shows how much can be learned from:

- drones,

- photo-ID methods,

- and repeated local monitoring.

Science doesn’t always require a ship and a million-dollar grant. Sometimes, it starts with being in the right place twice.

Let’s Explore Together

To keep the conversation going:

- Could similar events be happening but going undocumented in your region?

- How would you design a low-cost monitoring system for species shifts?

- If you were on this research team, what question would you investigate next?

The ocean is rewriting its rules in real time. And now, thanks to this study, we have a front-row seat.