What Really Helps Migrants Thrive in New Countries?

Across the world, more than 270 million people live outside the country where they were born. But here’s the twist: adapting to a new country isn’t mostly about learning new customs—it’s about whether people feel connected or shut out.

That insight comes from one of the largest studies ever conducted on migrant adaptation. Researchers analyzed over 5,000 effects from more than 1,100 studies, covering over half a million migrants—including refugees, international students, workers, and expatriates—living in dozens of countries.

What they found challenges some long-held assumptions.

We Thought Culture Was the Main Challenge. It’s Not.

For decades, research and policy have focused on culture learning: language skills, local norms, and how “far apart” cultures are. It makes intuitive sense. Moving from rural Nigeria to London, or from Brazil to Japan, feels like crossing invisible borders of behavior and meaning.

But when the data were stacked side by side, culture turned out to matter less than expected.

Instead, two forces dominated migrant adaptation across nearly every context:

- Stressors, especially discrimination and migration-related stress

- Social resources, especially feeling connected and not lonely

In other words, migrants struggle not because they don’t understand the culture, but because they are isolated or pushed away.

And here’s where it gets interesting.

A Story That Repeats Across the World

Picture three people:

- A nursing student from India studying in the UK

- A construction worker from Guatemala in Mexico City

- A refugee family rebuilding life in Germany

Their legal status, income, and language skills differ. But the study shows their adaptation follows a similar pattern.

When migrants feel excluded, discriminated against, or overwhelmed, their psychological well-being drops. When they feel socially connected—even to just a few people—their ability to function, cope, and “fit in” improves dramatically.

The problem → twist → solution looks like this:

- Problem: Migration brings unavoidable stress

- Twist: Cultural distance isn’t the biggest driver of success or failure

- Solution: Social connection consistently protects migrants across contexts

Why Loneliness Hits So Hard

Loneliness showed up as one of the strongest predictors in the entire analysis.

Think of loneliness like walking through a city where no one makes eye contact. You may learn the streets quickly, but everything feels heavier. That emotional weight affects sleep, motivation, confidence, and learning—core ingredients for adaptation. The data show that not feeling lonely is strongly linked to better psychological and social adaptation, regardless of country or migrant type.

And loneliness isn’t just personal—it’s structural.

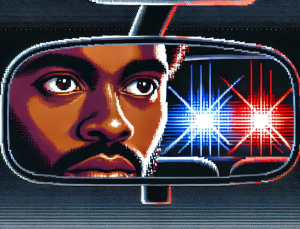

Discrimination: The Most Consistent Barrier

Among all stressors, perceived discrimination stood out. Unlike some factors that varied by context, discrimination showed a strong, consistent negative relationship with how well migrants adapted socially, including their ability to participate, communicate, and feel at home in daily life.

This matters because discrimination doesn’t just hurt feelings. It limits opportunities:

- Fewer chances to practice language

- Less access to informal networks

- Lower trust in institutions

Over time, discrimination becomes a wall—not a misunderstanding.

A Surprising Hero: Supervisors

One unexpected finding surprised even the researchers.

Support from supervisors—teachers, professors, managers, or workplace leaders—had one of the strongest positive links to migrant adaptation.

Think about why. Supervisors control schedules, expectations, feedback, and access to resources. A small act—clear instructions, encouragement, flexibility—can lower stress and open doors.

This finding is powerful because it’s actionable. Training supervisors to better support migrants could yield outsized benefits, especially in schools and workplaces.

What This Means in the Real World

If you work in education, public health, NGOs, or local government, this study sends a clear message:

- Integration programs shouldn’t focus only on language and culture

- Policies must actively reduce discrimination

- Social connection is not “soft”—it’s foundational

For resource-limited settings, this matters even more. Building community spaces, mentorship programs, and inclusive institutions may be more effective than expensive training alone.

A Note of Scientific Honesty

The authors are careful to say this: most studies were observational. That means we can’t prove cause and effect yet. Feeling connected may improve adaptation, or adapting well may help people connect. Still, when hundreds of thousands of lives point in the same direction, it’s a direction worth taking seriously.

Let’s Explore Together

- Could stronger social connection improve outcomes in your community?

- If you worked with migrants, what kind of support would you test first?

- What everyday problem do you wish science would study at this scale next?

Science moves forward not just through data, but through the questions we ask next.