Chimpanzees Caught Using Insects as First-Aid

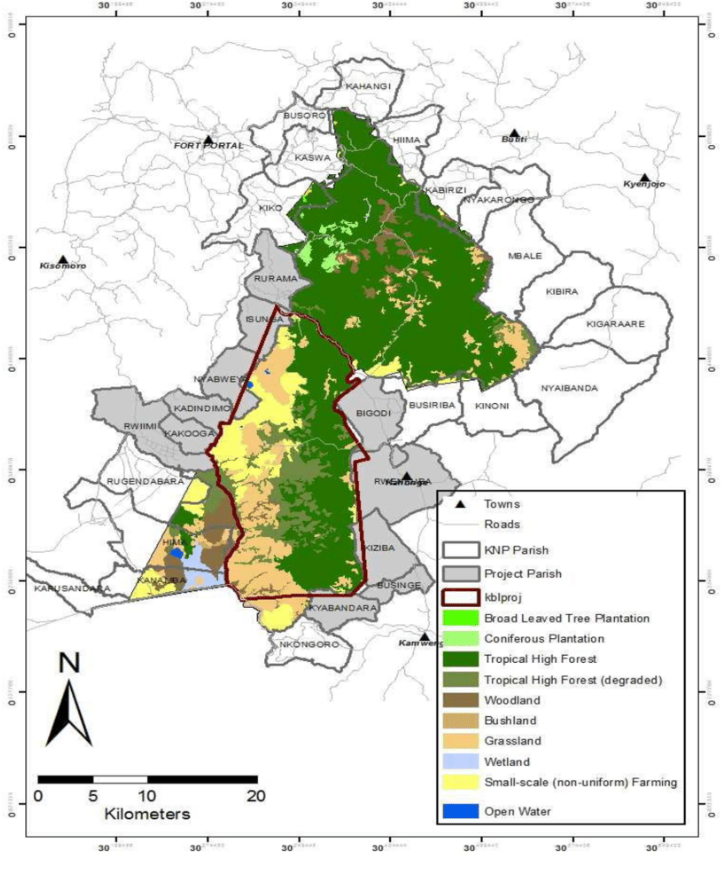

Picture this: deep in Uganda’s Kibale National Park, a young chimp named Damien gets a nasty gash on his calf. Instead of just licking the wound or ignoring it, he grabs a flying insect, presses it against the cut, and carefully rubs it across the open skin. A few moments later, his sister joins in, applying her own captured insect directly to her brother’s injury.

Sounds like the start of a superhero origin story, but it may rewrite what we know about the roots of medicine.

A new study of the Ngogo chimpanzees in Uganda reports something astonishing: wild chimpanzees applying insects to open wounds, not just on themselves but sometimes on others. This is the first documented case outside Gabon, where Central African chimps were earlier spotted doing the same thing. The finding could shed light on how the earliest humans first discovered the healing power of nature.

From Grandma’s Remedies to Chimp First Aid

Human societies have been using plants, fungi, and even insects—as well as other natural substances—as medicine for thousands of years. From Neanderthals chewing on chamomile to Chinese healers cataloging hundreds of insect species for their medicinal properties, traditional remedies have long been an integral part of survival.

But here’s the kicker: scientists think we may have learned some of these tricks from animals. Observing which plants or substances animals use when they’re sick may have tipped off ancient humans to what worked.

This study flips the lens: what if chimpanzees themselves are pioneering their own version of first aid?

The Three Bug-Healing Events That Stunned Scientists

The researchers observed five bug-related wound treatments, but three were so clear they’ve become case studies.

- Fricka’s DIY Fix – An adolescent female pressed an insect to her thigh wound, reapplied it when it slipped off, and even appeared to ingest some white residue from the bug. Was she after pain relief? Infection-fighting compounds? We don’t know yet.

- Damien the Inventor – An adolescent male caught a flying insect, pressed it against his calf wound, and reapplied it several times. He even paused to inspect the bug before discarding it.

- Sisterly Care – Damien’s sister, Etta James (yes, that’s her real name), caught her own insect and carefully applied it to Damien’s wound. This wasn’t just self-care—it was other-care.

Each case followed a strikingly similar pattern: catch insect, immobilize it (often by squeezing it with the lips), press it against the wound, move it across the surface, then either discard or reapply.

Why Insects? The Science Behind the Squirm

It might sound gross, but insects are medicine powerhouses. Green bottle flies, for example, have been used in modern medicine as “maggot therapy” because their secretions can disinfect wounds, eat dead tissue, and promote healing. Honeybee venom has antimicrobial effects. Silk moth extracts have been tested for wound recovery.

So, when chimps consistently choose flying insects for wound care, it raises a tantalizing question: do they know something we don’t? Are they instinctively tapping into an ancient insect pharmacy?

Copycats, Curiosity, and Culture

The story gets even juicier when you factor in social learning. In several cases, other chimps were observed peering closely while one applied an insect. In chimp society, peering is like watching a YouTube tutorial—one individual studies another’s behavior to copy it later.

That’s exactly what seemed to happen when Etta James watched Damien treat himself before she treated him. Could insect first aid be spreading as cultural knowledge, passed down like tool use or grooming techniques?

If so, this means chimpanzees aren’t just experimenting with natural remedies—they may be teaching each other how to heal.

Medicine Meets Empathy

Perhaps the most profound part of this discovery is the possibility of prosocial behavior. Applying an insect to someone else’s wound isn’t about survival of the fittest—it’s about helping another. Some scientists argue this hints at the roots of empathy.

Archaeologists already know Neanderthals cared for sick and injured group members. If our chimp cousins are showing similar instincts, we may be looking at a shared evolutionary seed of compassion.

What This Means for Us

This quirky animal fact is a window into how medicine and empathy might have evolved hand in hand. Watching chimps experiment with insects makes us ask big questions:

- Did the first humans learn about healing by copying animals?

- Is caregiving hardwired into our DNA, older than fire or farming?

- Could studying chimp “bug medicine” uncover new compounds for modern treatments?

What’s clear is that preserving wild chimpanzee populations is about more than saving an endangered species. It’s about preserving the cultural and biological experiments that can still teach us about ourselves.

Let’s Explore Together

The idea of chimps pressing bugs into wounds may seem strange, but it opens the door to some of the most exciting questions about who we are and where we came from.

Now it’s your turn:

- How do you see this research affecting your view of medicine?

- What would you do if you saw a chimp apply a bug to a wound—film it, run away, or take notes?

- What’s the coolest science fact you’ve learned recently that made you go, “Wait, what?!”

Drop your thoughts in the comments, share this with your most science-curious friend, and let’s keep exploring the wild, weird, and wonderful world of science together.