A 400-Year-Old Shark Still Has Working Eyes

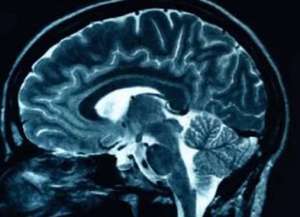

For decades, scientists assumed the Greenland shark was almost blind.

The new data say the opposite: its eyes still work—and they may hold clues to how tissues survive for centuries.

The Greenland shark lives where sunlight barely reaches. It moves slowly through Arctic waters, often with parasites clinging to its eyes. Some individuals alive today may have been born before the Industrial Revolution. If any animal were expected to lose its vision, this would be it.

But a new study delivers a surprise. Not only does the Greenland shark still see—it has a visual system finely tuned for darkness and remarkably well preserved over time. And that discovery reshapes how we think about aging, adaptation, and resilience in extreme environments.

Seeing in Near-Darkness Is Like Listening in a Whispered Room

Imagine trying to hear a single voice in a packed room at night. You don’t need volume—you need sensitivity.

That’s how vision works in the deep sea.

Most animals rely on two kinds of light-detecting cells. One works best in bright conditions. The other is designed to catch even the faintest glimmer. The Greenland shark has committed fully to the second strategy.

The researchers found that its retina is composed almost entirely of cells specialized for low-light vision. These cells are longer, tightly packed, and optimized to capture scarce photons—exactly what you would want thousands of meters below the surface, where sunlight fades into blue haze.

This isn’t broken vision. It’s a focused vision.

But the surprise wasn’t just structure. It was longevity.

The Big Question: Shouldn’t a 100-Year-Old Eye Be Falling Apart?

In humans, retinal cells slowly die as we age. Even healthy eyes lose light-sensing cells over time. If people lived for 400 years, scientists estimate we would lose most of our night vision long before the end.

So the team looked for damage.

They searched the shark’s retina for signs of dying cells, broken DNA, or tissue breakdown. They expected to find scars of age.

They found none.

Even sharks estimated to be more than a century old showed no obvious retinal degeneration. The cellular layers were intact. The circuitry was complete. The system still looked alive and functional.

That raises a deeper puzzle. How does a nervous tissue—normally so fragile—last this long?

The Shark Didn’t Preserve Everything—Only What It Needed

The Greenland shark didn’t keep a “full-service” eye. Instead, evolution made trade-offs.

Genes linked to bright-light and color vision were damaged or shut down. The shark essentially abandoned visual abilities that don’t matter in darkness.

At the same time, genes needed for dim-light vision were not only intact—they were active. The shark’s retina still produces the proteins required to detect light, transmit signals, and process visual information.

Think of it like a phone switched to ultra-low-power mode. Features you don’t need turn off. Core systems stay online.

That selective simplification may be part of the secret.

The Retina Runs on Cold-Proof Chemistry

Cold makes cell membranes stiff, like butter straight from the fridge. That’s a problem for vision, because light-detecting proteins need flexible membranes to work.

The Greenland shark solves this with chemistry.

Its retinal cells are packed with special fats that stay fluid at low temperatures. These fats help visual proteins function efficiently even in freezing water. Compared to land mammals, the shark’s retina contains unusually high levels of these cold-adapted lipids.

This matters far beyond sharks.

In many parts of the world—high mountains, polar regions, deep oceans—organisms face extreme cold. Understanding how cells stay functional under those conditions could inform everything from biology to medicine to materials science.

But perhaps the most intriguing clue comes from something we rarely notice.

Repair May Matter More Than Avoiding Damage

The study also found that the Greenland shark’s retina strongly expresses genes involved in DNA repair. These genes help fix molecular damage before it turns into cell death.

In humans, failures in similar repair systems lead to early vision loss and accelerated aging. The shark appears to run these systems continuously, quietly maintaining its tissue year after year.

This suggests a shift in thinking.

Instead of asking, “How do we stop damage from happening?”

We might ask, “How do we repair damage so well that aging slows down?”

That idea resonates far beyond marine biology.

Even Parasites Don’t Shut the Lights Off

Greenland sharks are famous for having parasites attached to their eyes. For years, these were assumed to block vision completely.

The researchers tested that assumption directly.

They measured how much light actually passes through the shark’s cornea—and found that plenty still reaches the retina, especially in blue wavelengths common in deep water. Even with parasites present, the eye still works

Once again, the story flips.

What looked like impairment turns out to be resilience.

Why This Matters—Especially Outside the Lab

For scientists and students in rapidly changing or resource-limited environments, this study carries a powerful message.

Nature doesn’t always optimize for speed, brightness, or abundance. Sometimes it optimizes for endurance.

The Greenland shark shows that:

- Complex systems can be simplified without failing

- Long-term maintenance may matter more than peak performance

- Repair and resilience can outperform replacement

These lessons apply to ecosystems under stress, to human health, and even to how we design technologies meant to last.

And we’ve only just started asking the right questions.

Let’s Explore Together

- Could this kind of “maintenance-first” biology inspire new approaches to aging or medicine?

- If you studied this shark next, what tissue or system would you examine?

- What everyday problem in your community could benefit from thinking about endurance instead of efficiency?

Science gets more exciting when it reminds us how much we still don’t know—and how much the world has already figured out.